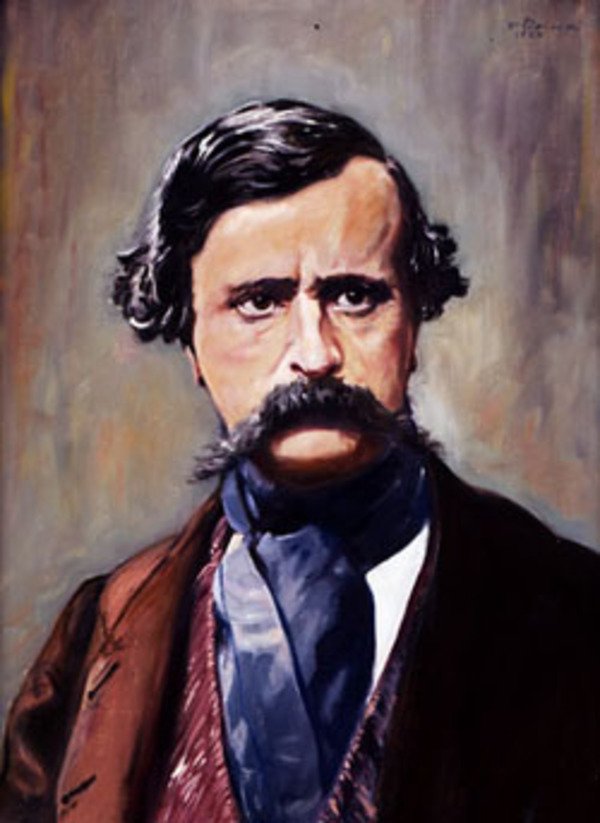

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BLANSHARD, RICHARD, governor; b. 19 Oct. 1817 in London, England, son of Thomas Henry Blanshard, a well-to-do merchant; m. 19 May 1852 Emily Hyde of Aller, Somerset; they had no children; d. 5 June 1894 in London.

Richard Blanshard received a ba from Cambridge in 1840 and an ma four years later. Having been admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1839, he was called to the bar on 22 Nov. 1844. Instead of practising law he elected to travel, spending “upwards of two years” in the West Indies. He served in India during the Sikh War of 1848–49, and at the end of the campaign was decorated for bravery. Although he was offered a commission in the British army, he preferred to return to England. A relative, possibly a friend of Sir John Henry Pelly, the London governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, had written to tell him that Vancouver Island was about to be colonized by the HBC and had intimated that he could become its first governor. Blanshard reached London in late June 1849, and Pelly promptly recommended him for the post. His commission was dated 16 July. He accepted the position without salary on the understanding that he would receive a grant of 1,000 acres in the colony.

Instead of sailing on the HBC’s annual supply ship, Blanshard travelled by the West Indian mail packet to Panama, and thence to Peru, where he boarded hms Driver. His arrival at Fort Victoria (Victoria, B.C.) in March 1850 was inauspicious: an unseasonal storm had dumped a foot of snow on the area, and the infant colony had no accommodation to offer him. On 11 March, in the presence of assembled British subjects, he formally read his commission and instructions. A few days later Chief Factor James Douglas* confided to the governor of the HBC, Sir George Simpson*: “He is rather startled by the wild aspect of the country, but will get used to it.”

Blanshard’s tenure was both brief and unhappy. The company had initially recommended Douglas as governor, but the Colonial Office had suddenly bowed to political pressure in Britain against naming an HBC employee to the position, and the company was forced to seek another candidate. The HBC nevertheless appointed Douglas its agent for conducting the affairs of the colony in accordance with the charter of grant. Under the circumstances, conflict between the two men was almost inevitable. The situation was aggravated by the fact that the London directors did not always appreciate colonial realities. For example, they had promised Blanshard a government house, without considering that Douglas had neither the manpower nor the resources to construct one in time for his arrival. Consequently, Blanshard had to remain on board the Driver and then move to an empty storehouse in the fort until the house was ready in the fall. From the outset Blanshard was staggered by the high cost of living, and he was particularly annoyed to learn of the pricing policy at the HBC store, which discriminated against those who were not employees of the company. An even ruder shock occurred when he was informed by Douglas that the substantial estate he had expected to receive was to be a reserve attached to his office and not property deeded to him personally.

Blanshard’s instructions from the Colonial Office were to establish a bicameral legislature, but he soon discovered that virtually all the residents were employees of the HBC, few of whom possessed sufficient property qualifications even to vote. Similarly, he informed his superior, Lord Grey, the only persons eligible to serve on a council would be “completely under the controul of their superior officers.” He therefore decided not to act until instructed further on this point. The absence of independent settlers meant that there was, in fact, very little for a governor to do, and as his relations with Douglas cooled he began to associate with a growing band of critics of the HBC, such as Edward Edwards Langford and Robert John Staines*.

Meanwhile, deteriorating relations between coalminers and the HBC at Fort Rupert (near present-day Port Hardy) involved Blanshard in the one area in which he was relatively free to act, the administration of justice. The miners appealed to him, claiming the company manager had illegally incarcerated two of them following a work stoppage in April 1850 [see Andrew Muir*]. The governor commissioned HBC surgeon John Sebastian Helmcken* magistrate for the district and charged him with investigating the matter. Before Helmcken could take any action, the miners left for California. During the course of his subsequent inquiries three company sailors who had deserted and fled into the woods to escape arrest were killed by Indians. From the confusing and contradictory reports that followed, Blanshard became convinced that the officers of the company placed its interests ahead of those of the colony. He had to wait until October for a naval vessel to escort him to Fort Rupert. When a detachment of the Royal Navy was sent ashore to negotiate with the Newitty Indians for the surrender of the suspected murderers, the natives abandoned their village and the whites burned it to the ground. The following summer Blanshard ordered the destruction of another Newitty village, to which the Indians responded by executing the alleged murderers themselves. The Colonial Office complained to Blanshard about the inappropriateness of such indiscriminate punishment.

Throughout his stay in Vancouver Island, Blanshard suffered from “continual attacks of ague,” and after returning from Fort Rupert to Fort Victoria in November, having spent seven days in an open canoe, he became critically ill. He tendered his resignation and requested permission to leave the colony, but it took nine months for him to receive a reply. During this period he joined the critics of the HBC in disputing with Douglas over the amount of land the company was claiming for its fur trade reserves. He complained that the company was dilatory in getting land surveyed and succeeded in embarrassing Douglas by calling attention to an irregularity in the charges for goods used in treating with the Indians. In 1851, at the request of the HBC and of a group of independent settlers, Blanshard appointed a council consisting of Douglas, Chief Trader John Tod*, and James Cooper*, which first met on 30 August. Two days later Blanshard departed from the colony on the Daphne. While crossing the Isthmus of Panama he lost most of his luggage in a shipwreck on the Chagres River. To add insult to injury, on his arrival in London in November, he found that he had to pay some £300 for his passage home.

Back in England, Blanshard married and later appears to have inherited his father’s estate. In 1857 he testified against the HBC before the British parliament’s select committee on the affairs of the company [see Sir George Simpson]. At the time he was living at his country estate of Fairfield in Hampshire and had another, 1,000-acre estate in Essex. Following his wife’s death in 1866 he seems to have spent most of his time in Essex and London. He died at the age of 76, after suffering from poor health and possibly total blindness. His estate, which amounted to more than £130,000, was left to a niece and a nephew.

[The only Blanshard papers that have survived are his original correspondence with the Colonial Office (PRO, CO 305, esp. 305/2: 49 et seq.) and a few records from his governorship of Vancouver Island (PABC, Add. mss 611). This material should be supplemented by the James Douglas papers at PABC, especially his letters to the HBC, London (in PABC, A/C/20Vi2, and printed in HBRS, 32 (Bowsfield)) and his letter to Simpson of 20 March 1850 (in PAM, HBCA, DS/27); and by Helmcken, Reminiscences (Blakey Smith and Lamb). For Blanshard’s testimony before the select committee on the Hudson’s Bay Company see its Report at G.B., Parl., House of Commons paper, 1857 (session ii), 15, nos.224, 260.

Useful secondary accounts of Blanshard’s career include W. E. Ireland, “The appointment of Governor Blanshard,” BCHQ, 8 (1944): 213–26; W. K. Lamb, “The governorship of Richard Blanshard,” BCHQ, 14 (1950): 1–40; and Margaret A. Ormsby’s introduction to HBRS, 32. His role in the Fort Rupert affair is both complicated and controversial. The most complete account appears in B. M. Gough, Gunboat frontier: British maritime authority and northwest coast Indians, 1846–1890 (Vancouver, 1984), 32–49, but see also R. [A.] Fisher, Contact and conflict: Indian-European relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890 (Vancouver, 1977), 49–53. A brief note on Blanshard appears in Alumni oxonienses; the members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886 . . . , comp. Joseph Foster (4v., Oxford and London, 1888). j.e.h.]

James E. Hendrickson, “BLANSHARD, RICHARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blanshard_richard_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blanshard_richard_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | James E. Hendrickson |

| Title of Article: | BLANSHARD, RICHARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |