Source: Link

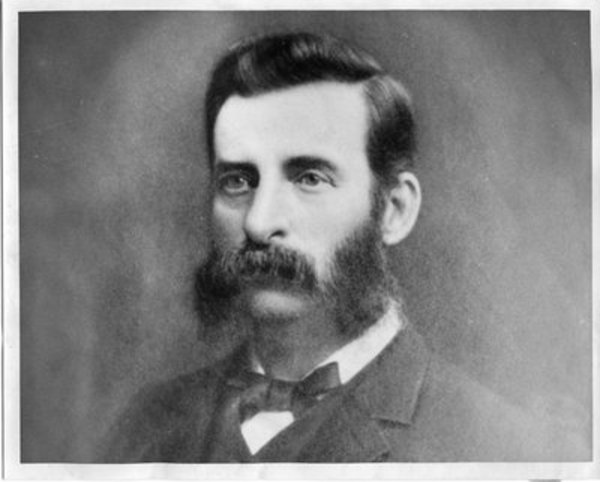

BLACKBURN, JOSIAH, publisher, journalist, and politician; b. 6 March 1823 in London, England, third son of the Reverend John Blackburn, a leading Congregational pastor, and Sarah Smith; m. 29 May 1851 Emma Jane Dallimore, and they had two sons and six daughters, including the journalist Victoria Grace*; d. 11 Nov. 1890 at Hot Springs, Ark.

Josiah Blackburn was educated at the City of London and the Mill Hill schools before immigrating to Canada West in 1850. He joined his brother John at the Paris Star in 1852 and also became involved in the Ingersoll Chronicle. That same year he purchased the weekly Canadian Free Press from James Daniell, holder of a $500 mortgage against William Sutherland, who had founded the paper in London, Canada West, in 1849. From a small printing office at the back of a dry goods store, Blackburn acted as editor, reporter, proof-reader, bookkeeper, collector, and canvassing agent. Early in 1854 the operation was expanded, and on 5 May 1855 Blackburn began a daily edition, the London Free Press and Daily Western Advertiser (after 1872 the London Free Press) which has continued to the present. The weekly Canadian Free Press was maintained under various mastheads until the 1880s. Josiah’s brother Stephen became a partner in 1858, assisting Josiah in reporting and in writing editorials, and was responsible for the business office until he left the firm in 1871. By 1860 the total circulation of all editions of the Free Press had reached 3,500 copies, second only to the Globe among Reform newspapers in Canada West. Although firmly established the journal nevertheless had a capital investment of only $2,000 in 1861; according to Blackburn, “My capital is felicity of expression.” There were 22 employees on the staff.

The Free Press, with new quarters after 1868, continued to prosper despite brisk competition in London, and on 3 July 1871 Blackburn formed a joint stock company, the London Free Press Printing Company, with John K. Clare, Henry Mathewson, and William Southam* as his copartners; he himself was no longer involved with the day-to-day operation of the newspaper. The new arrangement led to many important innovations. By 1873 the journal had new type, a new press, and special features. An evening edition and pyramid headlines, summarizing news stories in bold print, were introduced. Blackburn was also ahead of his contemporaries in instituting a policy of avoiding editorializing in reports of speeches.

Blackburn was active in politics, and from its inception the Free Press had a reputation for supporting Reformers. He was the Reform candidate for Middlesex East in the 1857–58 election, losing to Marcus Talbot, the editor of the rival London Prototype. Blackburn favoured reciprocity, retrenchment, temperance, and representation by population, and opposed separate schools and sabbath labour. According to the Hamilton Spectator, Blackburn would have been George Brown*’s “warming pan” in parliament.

The year 1858 was a frustrating one for Reformers, and by the year’s end Blackburn was questioning Brown’s leadership. In the furore caused by the celebrated “double shuffle” Blackburn took a different position from other Reform journalists, and from Brown and the Globe in particular. When the courts upheld the legality of the double shuffle he refused to impugn the motives of the judges [see William Henry Draper*], believing that, although it was unworthy and ill judged, it was not illegal. By April 1859 he was convinced that Brown was an impossible leader who could never achieve success especially since he had now alienated Lower Canadian Reformers. Blackburn’s personal attack on Brown raised speculation in some quarters that he was seeking a party realignment under the leadership of Louis-Victor Sicotte and John Sandfield Macdonald*, with the Free Press as official mouthpiece. By June a number of journals, notably the Hamilton Times, were supporting the Free Press position.

By July 1859, however, Brown had reasserted his leadership of the Reform party and by September he was advocating a party convention to reunite Reformers. The Free Press opposed suggestions that the union of the Canadas should be abandoned because traditional Reform goals seemed to be thwarted in it. Blackburn was also critical of the fact that the convention in November 1859 was to be an Upper Canadian affair at a time when cooperation with Lower Canadians was essential and when Reformers were criticizing Lower Canadian sectionalism. The convention organizers slighted Blackburn, who as a Reform candidate and editor should have been an ex-officio delegate, and did not admit him to the convention until proceedings were open to all journalists. The Free Press challenged the Globe’s interpretation of the major compromise of the convention, which called for the dissolution of the union and the creation of “some joint authority.” Blackburn ridiculed the outcome of the convention, and in particular challenged the right of Brown to dictate to the Reform party as if the Globe and Toronto had a monopoly on truth. That Blackburn considered running as an independent candidate in the by-election for Middlesex East in 1860 is a reflection of his view that “the position of affairs is many-sided” and that Reformers came in different shades. By April 1860 he was defending and cooperating with Sandfield Macdonald, who had boycotted the Reform convention.

When Sandfield Macdonald and Sicotte formed a new administration in May 1862, the Free Press became the most official mouthpiece of the government in the western part of Canada West. In 1862 Blackburn went to Quebec to undertake the management of a government newspaper. In August the Quebec Mercury was leased; Blackburn became publisher and George Sheppard editor. The Mercury was transformed into a daily on 12 Jan. 1863 and Blackburn continued with the newspaper until after the resignation of the government of Sandfield Macdonald and Antoine-Aimé Dorion* in March 1864.

Blackburn became a persistent advocate of coalition governments as the most effective means to pursue practical, short-term measures of reform. He readily accepted, therefore, the confederation coalition formed in June 1864, even though it included Brown and lacked the support of Sandfield Macdonald. The Free Press had reservations about confederation until the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences, when its practicality as a federal union with firm guarantees for Canada West was demonstrated. On the assumption that confederation meant independence, a favourable consequence of confederation, in Blackburn’s view, would be non-involvement in British affairs and a chance to reduce defence commitments; attacks were then made on the Free Press as an advocate of annexation to the United States since many Upper Canadians felt annexation would follow independence.

The resignation of Brown from the coalition cabinet in December 1865 coupled with Sandfield Macdonald’s selection as premier of Ontario in July 1867 reinforced Blackburn’s views, and made his transition to the support of Sir John A. Macdonald* and the Conservatives a smooth one. Blackburn was henceforth an invaluable asset to Conservative party organization in western Ontario. He became a close personal friend of John Carling*, the Conservative member for London in both the dominion and the Ontario legislatures. The Free Press had a wide distribution throughout western Ontario, and had a reputation for sound political judgements, “never prejudicing party interests by haste or immature consideration.” Blackburn was also relatively free to move where he was needed. One of the best examples of this occurred in 1872 when he went to Toronto to assist in establishing the Toronto Mail as an effective Conservative organ and foil to the Globe, thus meeting a need underlined by the defeat of the Sandfield Macdonald administration in December 1871. Blackburn remained chief of the staff at the Mail for about 15 months. But, though a strong Conservative publicist and organizer, Blackburn remained conscientious and independent in his approach to issues. A strong advocate of reciprocity in the 1850s, he gave only qualified support to the National Policy in the 1870s, after long argument.

Blackburn maintained an active interest in London In October 1875 he was on the executive committee of the London Musical Union. He was a promoter of the mechanics’ institute and, in 1881, was a charter member of the reorganized London Board of Trade. He also supported efforts to establish a branch of the provincial university in London. Along with his entire family Blackburn was rebaptized an Anglican on 23 Aug. 1866 in St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

During the 1880s Blackburn received two government appointments. In 1880 he was named census commissioner in western Ontario and in 1884 a commissioner for organizing a printing bureau at Ottawa. He investigated government printing establishments in Washington as well as some state capitals and his recommendations culminated in the establishment of the Department of Public Printing and Stationery in 1886.

At his death Blackburn left an estate with real and personal assets totalling nearly $20,000 and shares in the London Free Press Printing Company and Carling Brewing and Malting Company valued at an additional $35,000. He also owned 400 acres of Manitoba farm land.

Josiah Blackburn was one of the most important newspapermen of his day. He was also politically influential, whether as a supporter of George Brown, Sandfield Macdonald, or John A. Macdonald. His journalism and politics were both characterized by a conviction that rational discussion of the issues was important, and the belief that anything Toronto could do London could do as well.

Josiah Blackburn letters (copies at UWO) are in the possession of W. J. Blackburn (London, Ont.). [J. S. Macdonald], “A letter on the Reform party, 1860: Sandfield Macdonald and the London Free Press,” ed. B. W. Hodgins and E. H. Jones, OH, 57 (1965): 39–45. London Free Press, 1852–90. Mail, 1872–73. Quebec Daily Mercury, 1862–64. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1886). [Archie Bremner], City of London, Ontario, Canada: the pioneer period and the London of to-day (2nd ed., London, Ont., 1900; repr. 1967). C. T. Campbell, Pioneer days in London: some account of men and things in London before it became a city (London, Ont., 1921). History of the county of Middlesex, Canada . . . (Toronto and London, Ont., 1889; repr. with intro. D. J. Brock, Belleville, Ont., 1972). E. H. Jones, “The Great Reform Convention of 1859” phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1971); “Political aspects of the London Free Press, 1858–1867” (ma thesis, Univ. of Western Ontario, London, 1964). [H.] O. Miller, Acentury of western Ontario: the story of London, “The Free Press,” and western Ontario, 1849–1949 (Toronto, 1949; repr. Westport, Conn., 1972). Fred Landon, “Some early newspapers and newspaper men of London,” London and Middlesex Hist. Soc., Trans. (London, Ont.), 12 (1927): 26–34. H. O. Miller, “The history of the newspaper press in London, 1830–1875,” OH, 32 (1937): 114–39.

Elwood H. Jones, “BLACKBURN, JOSIAH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blackburn_josiah_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blackburn_josiah_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Elwood H. Jones |

| Title of Article: | BLACKBURN, JOSIAH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |