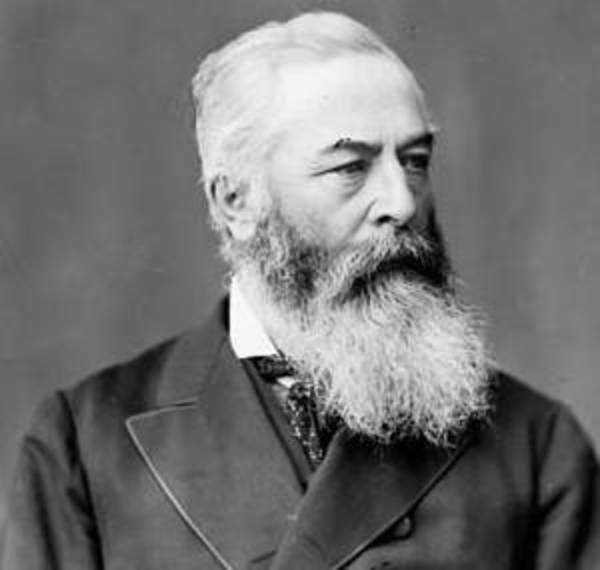

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BERGIN, DARBY, physician, militia officer, stockbreeder, office holder, politician, and railway entrepreneur; b. 7 Sept. 1826 in York (Toronto), eldest son of William Bergin and Mary Flanagan; d. unmarried 22 Oct. 1896 in Cornwall, Ont.

Darby Bergin was the son of an Irish Catholic immigrant who had established himself as a merchant in York (Toronto) in 1820. Darby attended Upper Canada College and, probably in 1844, entered McGill College in Montreal; at the time of his enrolment his residence was listed as Cornwall. He received his md at a special convocation in September 1847 shortly after his twenty-first birthday and established a practice in Cornwall, which remained his principal residence for the rest of his life. Bergin served as the administrator of the typhus sheds there in 1848 and a few years later cared for the Indians at Saint-Régis (Akwesasne), Lower Canada, during a smallpox epidemic. Little more is known of his medical practice except that, according to a contemporary biographical source, he had an “extensive ride and a remunerative business.” He was also involved in medical politics, serving as the founding president of the Eastern District Medical Association and as president of the St Lawrence and Eastern District Medical Association. For the major controlling body of the medical profession in the province, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, he was an examiner in midwifery and in surgical anatomy, and he served as vice-president of its council in 1880–81 and as president in 1881–82 and 1885–86.

In the Cornwall area Bergin and his brother John, a lawyer, operated the Stormont Stock Farm, devoted largely to breeding trotting horses and shorthorn cattle. Around 1880 they owned two distinguished stallions, Ringwood and Midway. Darby also participated in civic affairs as trustee of the grammar school and member of the town council. In 1872 he was elected by acclamation as a Liberal to represent Cornwall in the House of Commons. When Alexander Mackenzie came to power the following year Bergin hoped to obtain a cabinet post, but he was excluded in favour of another Catholic from the Cornwall–Glengarry area, Donald Alexander Macdonald. Bergin’s conflict with the Macdonald family and the split among the region’s Liberals became aggravated when Alexander Francis Macdonald, a brother of Donald Alexander and a supporter of the Mackenzie government, ran against Bergin in Cornwall and defeated him at the elections of 1874. When Bergin regained his seat in 1878, he had become an acknowledged supporter of the Conservative party. He was unseated in December 1879, when his election was controverted before the Court of Queen’s Bench for Ontario, but, although several men were declared guilty of “corrupt practices” in the election, the judge specifically noted that Bergin had been found not to have known about or consented to the practices. He was re-elected on 27 Jan. 1880 and retained his seat until his death.

Bergin was said to have been a gifted parliamentarian and a fluent speaker. His legislative interests lay primarily in two areas, public health and transportation. Activities in the domain of public health included attention to the health of farm animals; in 1879 he spoke to the house on diseases in cattle, and five years later, as a member of the committee of supply, he supported government expenditures on quarantine. An interest in these matters must have enhanced his popularity among his largely rural constituents. Bergin opposed the Canada Temperance Act of 1878 [see Sir Richard William Scott*]. He made a vigorous speech in the commons in 1887, pointing out the disastrous effect the legislation (which in fact promoted prohibition, not temperance) had had on public morality in Cornwall. Where drunkenness had previously been unknown, he said, there were by that time “from 100 to 150 unlicensed places dealing out poison morning, noon, and night, Sabbath day and week day.”

Bergin also made an important contribution in the area of labour and industrial health. Motivated perhaps by conditions in the Cornwall textile industry, between 1879 and 1886 he introduced a series of private member’s bills to regulate the employment of children and women in factories. The first one – prohibiting the employment of children under the age of 12, stipulating that no child or woman could work more than 10 hours a day, and prescribing standards of cleanliness and safety to be enforced by government inspectors – did not receive more than first reading. A second one, revised and expanded to include some 200 clauses, was introduced in the 1880–81 session, but debate was deferred and a commission of inquiry appointed. The government then introduced its own factory bills in 1882 and 1883. The proposed legislation was debated but, although supported by the minister of inland revenue, James Cox Aikins*, and the minister of justice, Sir Alexander Campbell, it was ultimately withdrawn because critics such as Senator Robert Barry Dickey claimed the regulation of labour lay outside dominion jurisdiction. Bergin continued to introduce private member’s bills, refined to avoid conflict with the powers of provincial legislatures, but these too fell victim to party politics and disputes over jurisdiction. Although the factory bills introduced in the dominion parliament were not passed, many of their clauses served as the basis for significant provincial legislation such as the Ontario Factories Act of 1884. A federal royal commission on the relations of labour and capital [see James Sherrard Armstrong*] was set up in 1886.

Some ambivalence, presumably rooted in party politics, is evident in Bergin’s concerns with transportation. He was often severely critical of Liberal expenditures on railways in the mid 1870s, yet he could not resist the draw of the enormous expansion of railway construction. He was the principal promoter of the Ontario Pacific Railway Company, which was to build a line from Cornwall to Ottawa, and in 1882 he introduced a bill petitioning for incorporation of the railway company, to which royal assent was given on 17 May. By 1886 he had become president of the company and served in that capacity until his death in 1896, when his brother John succeeded him. The company, presumably not hindered by Bergin’s service on the select standing committee on railways, canals, and telegraph lines, was successful in obtaining public funds. In 1884, for example, it received a subsidy of $262,400 for a branch line from Cornwall to Perth. According to the act granting the subsidy, the line was to be begun within two years and completed within four. However, it was only after Bergin’s death, 12 years later, that a railway through Cornwall was completed by the New York Central Railroad Company. Bergin was also a supporter of the expansion of the Cornwall Canal, which in 1889 was the subject of one of his most significant parliamentary speeches; he urged the appointment of a royal commission to examine the plans, about which there had already been considerable disagreement among various engineers.

Bergin’s career in the militia seems to have begun at the time of the Trent affair in November 1861 [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*], when he raised the 1st Volunteer Militia Rifle Company of Cornwall. His effort was one of many similar patriotic responses to the realization that war with the United States was possible and that, without militia support, responsibility for defence would fall to a few British regulars. His connection with the Canadian military would continue throughout his life. In 1866, during the Fenian raids, he became major of the company, and on 3 July 1868 the 59th (Stormont and Glengarry) Battalion of Infantry was organized, with Bergin as lieutenant-colonel.

His most important military post, however, was that of surgeon general of the expedition under Frederick Dobson Middleton sent to subdue the forces of Louis Riel* in the northwest in 1885. Most militia units had their own surgeons, but until this time overall planning and organization of a medical service had devolved largely upon the British army. Moreover, medical training in the militia was often negligible, with the government consistently ignoring all recommendations for improvement as well as appeals for instruments and for fresh medicines to replace those that had grown stale from years in storage. When the rebellion broke out in March, the minister of militia and defence, Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, first sought aid from Dr Campbell Mellis Douglas, vc. Douglas began the task of reorganization, but he believed that it was impossible without help and that the Americans should be approached. Caron, however, believed Canada was capable of managing its own affairs and, perhaps having lost faith in Douglas, asked Bergin on 1 April to replace him. Bergin accepted the position even though he was also an mp; this combination of duties, although not unique, provoked some criticism in parliament the following month by Liberals concerned that Bergin was receiving two salaries from the public purse. Caron praised Bergin’s work, however, and stated that he was paid as any officer on active service would be.

Meanwhile, Bergin was trying to create a medical service out of chaos. As he wrote in his report of 13 May 1886, “There was no fixed Departmental Medical Staff, no Field Hospital or Ambulance Service, no organized Corps of Nurses, no fixed method of recognizing such societies as the St. John’s Hospital Aid Society, the Red Cross, and other similar charitable associations.” Four days after assuming his post Bergin appointed a staff, including Senator Michael Sullivan, a physician, as purveyor general, and Dr Thomas George Roddick* as deputy surgeon general. He organized two field hospitals staffed by volunteer medical students from Ontario and Quebec and put Douglas and Dr Henri-Raymond Casgrain in charge of them. Thanks to Bergin’s energy and authority, the deputy surgeon general was in Winnipeg with his unit by 12 April, only 13 days after Douglas had conceded his inability to organize the service without outside help. Meanwhile Bergin continued to direct the service from Ottawa.

The medical personnel had the good fortune to travel west via the United States, and thus were spared the discomforts and hazards of travel along the line of the unfinished Canadian Pacific Railway. Although Douglas had not succeeded in creating a militia medical service, he lacked neither courage nor determination; having travelled alone, by canoe and overland, more than 200 miles in five days, he arrived to help treat the wounded at Fish Creek (Sask.). He served faithfully under Bergin and Roddick. Several regimental surgeons, however, declined to accompany their battalions and were replaced by volunteers, of whom there was no shortage. The plethora of medical student volunteers created its own problems, and Bergin wisely decided that they should be paid in order to ensure their continued commitment. Along with the physicians and the medical students went at least a dozen nurses, including L. Miller, head nurse at the Winnipeg General Hospital, who took charge of the many casualties sent to Saskatoon.

The problems Bergin faced in administering the medical service were substantial. First, he was without Canadian precedents to guide the work of the medical teams. The problem of supplying an army was acute in an area that was thinly populated and lacking supplies of all kinds, including medicine. The citizens of Manitoba competed with the Hudson’s Bay Company for the riches they believed would flow from the public purse to those providing food, clothing, and other necessaries. Medicines, instruments, and appliances were ordered in Montreal and New York, and had to be transported to the northwest over a tortuous route. Though the rebellion was short, casualties were sufficiently heavy to test the medical service. It seems to have performed its tasks well, and one of the wounded publicly praised it, commending both the care and, perhaps surprisingly, the food. Even more significant, there is no evidence of serious criticism in the press. Bergin’s efforts, then, should be judged successful: the casualties of a substantial Canadian military force in the field were for the first time cared for by a Canadian medical service.

The service was dismantled after the emergency, however, and Bergin failed to persuade the government to create a permanent medical staff corps to help prevent repetitions of the chaos that had existed initially in 1885. He had outlined a course of study for incoming officers and suggested that prospective military surgeons should be required to demonstrate competence in the field. Yet he had also foreseen the flaw that the government would find in his scheme, noting that it would cost money. The kind of changes Bergin wanted would not be made until many years later: three years after his death George Ansel Sterling Ryerson*, who had served as one of his field surgeons in 1885, echoed his former commander in calling for the creation of a Canadian militia medical corps. After 1898 Frederick William Borden*, the minister of militia and defence, helped to institute a number of reforms and in 1904 the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps finally came into being.

Following the rebellion Bergin had returned to his parliamentary duties and to his work with various medical associations. In 1886 he was promoted colonel. Ten years later he succumbed to an unidentified illness. A friend, writing to Wilfrid Laurier* on 14 Oct. 1896, said that Bergin was making “slow but sure recovery,” but he was mistaken. The doctor died eight days later. Unmarried, he left his entire estate to his brother John. When the will was probated his shares in the Ontario Pacific Railway were found to be worthless, and his estate was valued at less than $7,000, not an impressive testimonial to a lifetime of “remunerative practice,” public service, and railway speculation. He had, however, been well liked and admired by his contemporaries; in 1892 writer Graeme Mercer Adam* paid him the following tribute: “Personally he is of a most genial and kindly nature, and his many estimable qualities secure for him universal respect and esteem.”

Darby Bergin’s report as surgeon general of the militia during the North-West rebellion appeared in Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1886, no.6a, app.5, and was reprinted in The medical and surgical history of the Canadian North-West rebellion of 1885, as told by members of the hospital staff corps (Montreal, 1886). A speech he delivered in the House of Commons was published as The Cornwall canal; its location and construction, breaks and present condition . . . ([Ottawa], 1889).

AO, MS 162; RG 22, ser.198, no.1817. McGill Univ. Arch., RG 38, c.11–c.12, 1844–45, no.18. NA, MG 26, G: 8265, 14075; MG 27, I, E16; RG 9, II, A3, 13, Bergin letter-book. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1880: 2: 1881: 559; 1885: 1914; 1887: 942; Journals, 1882: 74, 518; 1883, app.l; 1884: 407. Dominion Medical Monthly and Ontario Medical Journal (Toronto), 7 (July–December 1896): 635–36. G. [A.] S. Ryerson, The soldier and the surgeon (Toronto, 1899). Telegrams of the North-West campaign, 1885, ed. Desmond Morton and R. H. Roy (Toronto, 1972). Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal), 2 Feb. 1879. Montreal Daily Star, 22 Oct. 1896. Canadian biog. dict. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). CPC, 1873. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Prominent men of Canada . . . , ed. G. M. Adam (Toronto, 1892), 410–13. Elinor Kyte Senior, From royal township to industrial city: Cornwall, 1784–1984 (Belleville, Ont., 1983). H. E. MacDermot, History of the Canadian Medical Association (2v., Toronto, 1935–58), 1. Desmond Morton and Terry Copp, Working people: an illustrated history of the Canadian labour movement (Ottawa, 1980). G. W. L. Nicholson, Seventy years of service: a history of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (Ottawa, 1977). Swainson, “Personnel of politics.” J. F. Cummins, “The organization of the medical services in the North West campaign of 1885,” Vancouver Medical Assoc., Bull., 20 (1943): 72–78. Eugene Forsey, “A note on the dominion factory bills of the eighteen-eighties,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 13 (1947): 580–83. J. P. McCabe, “The birth of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps,” United States Armed Forces Medical Journal (Washington), 5 (1954): 1016–24. Bernard Ostry, “Conservatives, Liberals, and labour in the 1880’s,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 27 (1961): 141–49.

Charles G. Roland, “BERGIN, DARBY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 2, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bergin_darby_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bergin_darby_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Charles G. Roland |

| Title of Article: | BERGIN, DARBY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 2, 2024 |