Source: Link

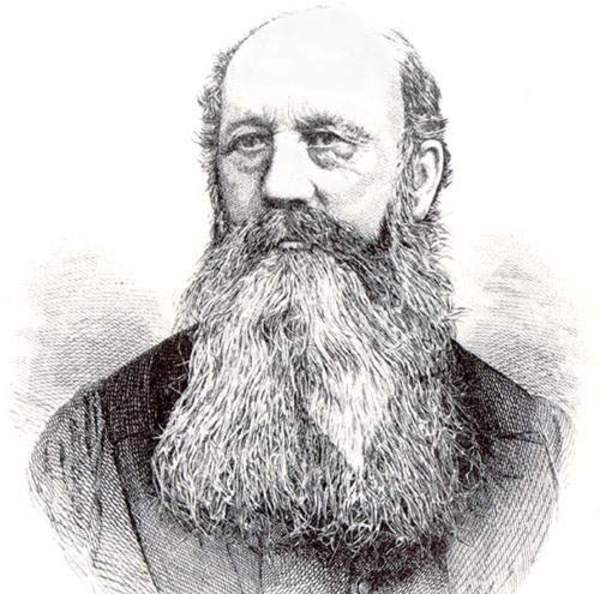

BENNETT, CHARLES JAMES FOX, merchant and politician; b. 11 June 1793 at Shaftesbury, Dorset, England, son of Thomas and Leah Bennett; m. 1829 Isabella Sheppard of Clifton (now part of Bristol), England; d. 5 Dec. 1883 at St John’s, Nfld.

That Charles James Fox Bennett’s family had a connection with the West Country–Newfoundland trade is probable since he was sent to St John’s in 1808, possibly as a clerk. Soon after the end of the Napoleonic wars he was in business on his own account in St John’s and in the early 1820s formed a partnership with his elder brother Thomas*. The firm of C. F. Bennett and Company was engaged in the general trade of the colony, supplying planters (especially in St Mary’s, Placentia, and Fortune bays), importing European merchandise, and exporting fish, usually on a commission basis. Unlike most Newfoundland trading firms, it seldom engaged in the seal-fishery, nor did it own many ships. The business prospered. By the mid 1820s the Bennetts owned a wharf and premises on Water St, and were becoming prominent citizens in St John’s. Thomas represented the firm on the chamber of commerce though Charles was elected president in 1836. Since Charles had married into Bristol society – there was a branch of the firm in that city – it seems that he spent a portion of each year in England.

The two brothers took part in the agitation for a representative constitution in Newfoundland in the 1820s, reflecting the views of most St John’s merchants. In January 1833 Charles became an aide-de-camp to Governor Thomas John Cochrane*, in June 1834 a justice of the peace, and in the same year a road commissioner. In the 1830s the brothers distinguished themselves from most Newfoundland merchants of the period by diversifying their business interests with a brewery, a distillery, and a sawmill. In 1847 they established a foundry at Riverhead, St John’s. They also built ships on their waterfront property. On his own account, Charles commissioned extensive mineral explorations along the island’s coast, and in the 1840s opened a slate quarry at Bay Roberts for which he brought in 12 to 14 Welsh miners; he also brought in a Welsh mining captain to search for potential mining sites in Placentia, Fortune, and Conception bays. In addition Charles was interested in farming, and in 1841 he was a founding member of the Agricultural Society. He eventually acquired 160 or more acres of land to the south of St John’s, where he established something of a model farm with his valuable imports of horses and horned cattle. All these activities reflect Charles Bennett’s life-long conviction that Newfoundland had considerable economic potential in addition to its fisheries, a point of view that was regarded as visionary in the first half of the 19th century. His capital, however, came from the traditional Newfoundland trade and his diversification coincided with a prosperous period for his firm which, in the 1840s and 1850s, became deeply involved in the lucrative Spanish trade, exporting fish in Spanish bottoms. The prosperity enabled the Bennett firm to experiment in the whale-fishery and to survive serious financial loss when their premises at St John’s and on the Isle of Valen (Placentia Bay) were destroyed by fire in 1846. Thomas Bennett gave up an active role in the firm in 1848.

Charles Fox Bennett’s political life began in 1842 when he announced his candidacy for St John’s in the election to be held for the Amalgamated Legislature in December 1842. Governor Sir John Harvey*, however, felt that the more moderate Thomas would stand a better chance of winning a Catholic seat and, urging him to run, promised Charles a place on the Legislative Council. Charles joined the council in January 1843. In the same year he became a governor of the Savings Bank and in 1844 an auditor of accounts for the government. His role on the Legislative Council was not a prominent one. He was a member of the Conservative group and joined it in voting against John Kent*’s 1846 resolutions in favour of responsible government. With the return to a bicameral legislature in 1848, Bennett lost his seat on the Legislative Council, but was reappointed in 1850 when he also joined the Executive Council.

In the tense political climate between 1850 and 1854, Bennett emerged as a leading and vocal Conservative who opposed the introduction of responsible government with an intensity which, an obituary noted, was deemed unreasonable even in the fevered atmosphere of that time. He was one of the most obdurate councillors in the debates over the redistribution of seats that was to accompany the introduction of responsible government. The debates produced a deadlock between council and assembly: the Liberal majority in the assembly, which had strong Catholic support, wished to double the existing number of assembly seats; the Conservatives considered this increase would give the Catholics an automatic majority and sought a redistribution that would ensure Protestants the edge or at least remove the chance of a Catholic predominance. Bennett argued that responsible government was unsuited to Newfoundland, not only because the colony was small and underdeveloped, but also because it would consolidate the Roman Catholic interests in the government. In February 1852 he told the Commercial Society of St John’s that a change in the constitution would hand over power to the Roman Catholic bishop, thus jeopardizing Protestant, particularly Anglican, rights.

For most of his life Bennett was active in the affairs of the Church of England in Newfoundland, and he was a keen supporter of Bishop Edward Feild*’s efforts to infuse the local church with Tractarian principles. He supported Feild’s contention in the 1850s that Anglicans had a right to separate schools, and led a campaign in the Legislative Council with Bryan Robinson and Hugh William Hoyles for a subdivision of the Protestant educational grant among denominations, an issue as emotive as responsible government in that it split Methodists from Anglicans and further alienated Anglican low churchmen from their bishop. The political result was to drive non-Anglican Protestants and Roman Catholics into a tactical alliance in favour of responsible government; the Liberal party, led by Philip Francis Little*, was then able to present itself as non-sectarian. This development influenced the Colonial Office’s decision in 1854 to grant responsible government to Newfoundland.

The introduction of responsible government in the following year was a Liberal triumph and Bennett suffered for his outspoken conservatism. He lost his seat on the Legislative Council, though not without a struggle. He challenged Governor Charles Henry Darling*’s right to remove him from the council, claiming his own right to a seat under the new constitution; his opinion, however, was rejected by both Darling and the Colonial Office. In 1856 when Bennett’s foundry and mill burned down, possibly as a result of arson, a mob tried to prevent the fire companies from reaching the blaze and succeeded in perforating the water hoses. The Liberals in 1858 turned the attention of the house to Bennett’s prospecting activities, in particular to his receipt between 1851 and 1854 of mining rights, with minimal obligations, to over a million acres of land situated in Bay d’Espoir, Fortune Bay, and the Burin Peninsula. The lease was referred to the imperial law officers who reported that it was ultra vires. In 1860 Bennett agreed to surrender the lease within two years if he could select in return ten mining locations from the initial grant. The agreement, however, was not incorporated in a local statute until 1904.

Bennett claimed that he was the victim of a “system of political and party persecution” which prevented him from forming a company, backed by English capital, to exploit minerals ‘round within the lease area. Surveys and the trial shafts which had been started in the early 1840s had already cost him £20,000, and Bennett bore a lasting resentment against those who had thwarted his plans. He found compensation at Tilt Cove in Notre Dame Bay where in 1857 a rich deposit of copper ore had been discovered by Smith McKay, a Nova Scotia prospector. McKay and Bennett went into partnership, using the latter’s capital, to open the Union Copper Mine which began production in 1864. It was the colony’s first significant mining venture, and by 1868 was providing employment for between 700 and 800 persons.

The dominant political issue of the 1860s in Newfoundland was confederation with the other British North American colonies. When the Quebec resolutions were published in St John’s in December 1864, Bennett stood out as one of the most important opponents of the proposed scheme. In a series of letters to the press in 1864 and 1865, he set out his opinion that the colony had nothing to gain and much to lose in transferring control of its natural resources to Canadians who would inevitably raise taxes and thereby dislocate the traditional patterns of Newfoundland trade; he urged the opponents of confederation to organize themselves, raising the frightening prospect that in confederation Newfoundlanders would be drafted into a Canadian army and “leave their bones to bleach in a foreign land, in defence of the Canadian line of boundary.” Although Bennett’s opposition to confederation was shared by many Newfoundland merchants, he was the most outspoken and one of the few prepared to campaign actively against union. Bennett did not emerge immediately as a party leader, however, because much of his time was absorbed by his mining and business interests; he spent every winter and spring in England where his wife was living. In the fall of 1867 and again in 1868 he returned to his press campaigns against confederation, urging that the economic plight of the colony should not be used by the confederates to stampede it into union. He contended that Newfoundland had “a temporary but painful malady,” and that it should wait for the cure which better times would bring. The confederates’ position that union was the only remedy was unacceptable to him. If Newfoundland were wisely and economically administered, he argued, its fishing, mineral, and land resources would be ample to support its population. Still believing that responsible government was a mistake for Newfoundland, he went so far as to suggest that a return to crown colony status was preferable to confederation.

It was agreed by all sides that the question of confederation should be settled by a general election. As the election of 1869 approached, a feeling permeated the community that the terms of union already under discussion would inevitably be endorsed. Bennett did not share this apathy. Having urged the opponents of confederation in November 1868 to organize themselves and apparently having extracted a promise from the Conservative premier, Frederic Bowker Terrington Carter*, that the election would not be held until the fall of 1869, Bennett left for England early in that year, sure that no effective campaigning would begin until the summer. It was clear by this time that he was emerging as the leader of a party against confederation. Wealthy, respected, and still energetic at the age of 76, Bennett put aside plans to retire to England and prepared to fight the move which he was convinced would ruin the colony (and, his opponents remarked, his industrial and mining interests). He returned to Newfoundland late in July with Walter Grieve, another wealthy anti-confederate merchant, and a 140-ton steamer in which to canvass the outports. He purchased control of the Morning Chronicle in St John’s and began a vigorous, outspoken campaign, aided by the confident atmosphere resulting from the best fishing season for a decade.

Bennett’s party was a curious amalgamation of old enemies. He and a minority of Protestant merchants and professionals who were former supporters of the Conservative party found themselves allied with the Catholic Liberals, who were opposed to the extinction of the responsible government for which they had fought and who feared that Newfoundland might suffer under Canadian domination as Ireland had under English. The crusade against Carter’s party and its pro-confederate platform gave Bennett’s party a superficial unity, and its success was overwhelming. Playing on the ignorance and patriotism of rural voters, the anti-confederates won 21 of 30 seats. Bennett was elected for the Catholic district of Placentia–St Mary’s, where his firm had once been active, and on 14 Feb. 1870 he became premier of Newfoundland. He did not hold a portfolio and did not take his salary as an assemblyman on principle.

Patrick Kevin Devine states that Bennett’s anti-confederate government was long remembered as “the best we ever had.” Its success was probably due to the relative economic prosperity of these years, which enabled the government to reduce taxes slightly, avoid borrowing, and increase expenditure – unique achievements for a Newfoundland administration. In accordance with Bennett’s personal interests, mining royalties were abolished and the grant to the geological survey increased. More money was allocated to roads and public works. The coastal steam service was improved and a direct service to England instituted. A police force, modelled on the Royal Irish Constabulary, was formed when the imperial garrison was withdrawn in 1870. In external relations, Bennett’s government cooperated with the imperial government. It acquiesced in the Treaty of Washington in 1871 and proved reasonably constructive over the difficult French Shore issue. But when Bennett started a lead mine at Port au Port on the west coast, an area in which he had long been interested, the inevitable protests from France claiming a breach of the treaty soured relations between Newfoundland and Britain. The Colonial Office saw Bennett’s decision to open the mine as a deliberate attempt to force its hand, and eventually made him close it.

In general, the Bennett government was sensible and carefully progressive. Yet his party was composed of such disparate elements that any premier would have found it difficult to weld them into a coherent unit. A fine campaigner, Bennett was not a politician and found the task impossible. He was unable to establish a firm personal ascendancy in the party with the result that his following was inherently unstable and the government could not effectively counter opposition moves to undermine its position. Opposition to confederation was the only issue binding Bennett’s party together. Realizing this, the Conservatives abandoned their advocacy of confederation about 1872, and concentrated on sectarian issues which would remove Bennett’s Protestant support. They attacked his close relationship with Bishop Thomas Joseph Power* of St John’s and his representing a Catholic district in the assembly. In the 1873 election Bennett could find no better platform than continued opposition to confederation; the Conservatives refused to take up the issue and instead accused him of selling out to the Roman Catholics. Furious, he launched a violent attack on the Orange order which played into his opponents’ hands. He won the election with 17 anti-confederate seats against 13 Conservatives but almost immediately there were defections to the Conservative party. On 30 Jan. 1874 he resigned. Another election in the fall of 1874 gave Carter’s Conservatives a clear majority. Bennett’s party was reduced to 13 members from Catholic ridings in the house of 30. In effect, the anti-confederate party had reverted to the old Liberal party with Bennett as its aging, improbable, and titular leader.

Bennett remained in the assembly until 1878, an increasingly isolated figure. The Liberals tended to look to Joseph Ignatius Little* for leadership, especially once it became clear that Bennett was the only member of the house opposed to the construction of a railway from St John’s to Halls Bay. His attitude in this matter was similar to his opinion about responsible government: railways were desirable per se and he had supported the construction of lines in the Tilt Cove and Betty Cove districts by mine owners, but Newfoundland was not ready for major lines. With a good sense that went unheeded, he argued that the colony needed more roads instead of an expensive railway which was certain to be its financial ruin and the cause of unbearable taxation for its fishermen. In this railway he saw a step towards confederation with Canada.

After 1878 Bennett’s only political role was to make clear his opposition to the contract for the railway in 1881. He was fully occupied with his business affairs and with a lengthy lawsuit against his mining partner, Smith McKay. Bennett filed for a dissolution of partnership and the sale of the mine, claiming that McKay owed him £19,000. The final result was the latter’s bankruptcy and Bennett’s assumption of complete control over the Tilt Cove operation in July 1880. When Bennett died in 1883, control of C. F. Bennett and Company passed to his partner Thomas Smith, and to his brother Thomas’ sons.

Aggressive and outspoken, politically conservative but economically progressive, Bennett did much to shape Newfoundland’s future. He was one of the first businessmen to invest significantly in local industries and was the pioneer of the colony’s mining industry. Above all, it was his stubbornness and determination which prevented Newfoundland from joining Canada in 1869. His electoral victory decided that for the foreseeable future Newfoundland would remain independent.

PANL, GN 1/3A, 1850–74; GN 1/3B, 1855–58, 1868–74; GN 2/1, 32–69; GN 3/2, 1831–80. PRO, CO 194/68, 194/144, 194/154, 194/179–87. Supreme Court of Nfld. (St John’s), Registry, Wills of C. J. F. Bennett, 1859, 1883. Bennettv. McKay (1874–84), 6 Nfld. R. 178, 241, 462. Bennettv. McKay (1884–96), 7 Nfld. R. 36, 44. Evening Telegram (St John’s), 18, 21–24 March 1881; 6 Dec. 1883; 6 March 1900; 24 May 1904. Morning Chronicle (St John’s), October-December 1867; October – December 1868; 31 July 1869. Newfoundlander, November 1827; 16 Dec. 1841; 19 Jan. 1843; 18 June, 30 July 1846; 2 Sept. 1847; 12 Jan. 1865. Public Ledger, December 1829; 4, 7 Nov. 1856; 30 Jan. 1857; 22 Feb. 1878. Royal Gazette (St John’s), 15 Jan. 1833, June 1834, June 1835, June 1841, 11 Dec. 1883. Times and General Commercial Gazette (St John’s), October–December 1867, October–December 1868. A. E. Chaulk, “The Chamber of Commerce . . . 1827–1837” (unpublished graduate paper, Memorial Univ. of Newfoundland, St John’s, 1969). Devine, Ye olde St John’s. Garfield Fizzard, “The Amalgamated Assembly of Newfoundland, 1841–1847” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Newfoundland, 1963). J. P. Greene, “The influence of religion in the politics of Newfoundland, 1850–1861” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Newfoundland, 1970). J. K. Hiller, “Confederation defeated: the Newfoundland election of 1869” (unpublished paper presented to the CHA, Quebec, 1976). Frederick Jones, “Bishop Feild, a study in politics and religion in nineteenth century Newfoundland” (phd thesis, Univ. of Cambridge, 1971). W. D. MacWhirter, “Apolitical history of Newfoundland, 1865–1874” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Newfoundland, 1963). E. C. Moulton; “The political history of Newfoundland, 1861–1869” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Newfoundland, 1960). Philip Tocque, Newfoundland: as it was, and as it is in 1877(Toronto, 1878). Wells, “Struggle for responsible government in Nfld.”

James K. Hiller, “BENNETT, CHARLES JAMES FOX,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bennett_charles_james_fox_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bennett_charles_james_fox_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | James K. Hiller |

| Title of Article: | BENNETT, CHARLES JAMES FOX |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |