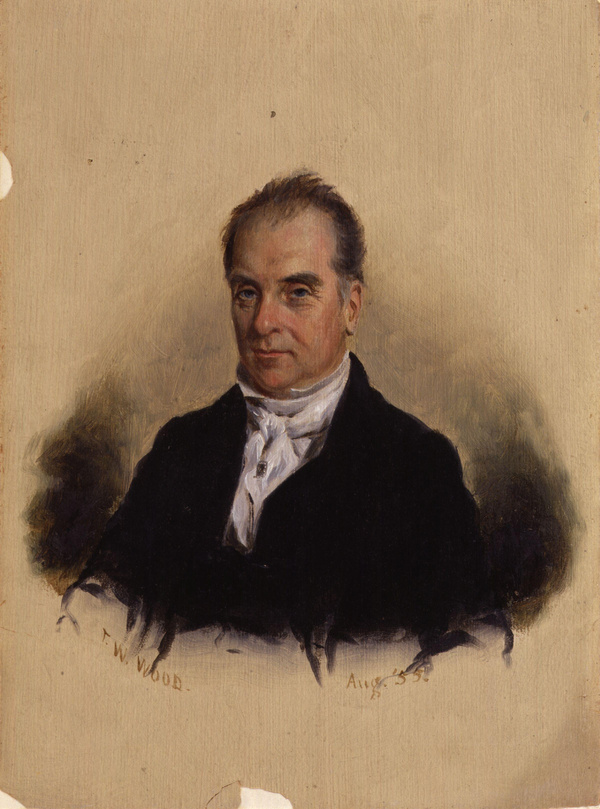

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BALDWIN, ROBERT, lawyer and politician; b. 12 May 1804 in York (Toronto), eldest son of William Warren Baldwin* and Margaret Phoebe Willcocks; m. 31 May 1827 Augusta Elizabeth Sullivan, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 9 Dec. 1858 near Toronto.

Robert Baldwin grew up in an extended, and somewhat closed, world of Willcockses, Russells, and Sullivans. Few institutions were as important to Upper Canadian society as the family, and the Baldwins’ relationships were especially close and affectionate. Unfortunately, the few documents surviving offer only glimpses into Robert’s childhood and adolescence. It is clear, however, from his conduct and utterance as an adult that his character was forged in boyhood under the influence of his urbane and talented father and perhaps more important his mother, whom he once described as “the master mind of our family” and who was probably responsible for Robert’s earliest education.

Robert was formally educated in York by John Strachan*. In 1818 William Warren said he was “as forward in point of education as our school here advances boys of his age. I shall keep him yet two years more at school . . . – I intend please God to bring him up to the bar.” It was, however, the expectations and standards of his parents, especially their exhortation to goodness and correct conduct, which remained with Robert. If anything, their hopes increased after the deaths of his younger brothers Henry (d. 1820) and Quetton St George (d. 1829). The legacy of principled life and uncompromised action defined Robert Baldwin in his public life, and it hobbled his spirit even as a young man. For he was, as he later put it, “a sceptic – may God forgive me though I hope not wholly an unbeliever.” Moreover, he was melancholic, sickly, and intensely emotional.

The defining characteristic of the teenager embarking on a career in his father’s legal office in 1820 was his idealization of women and his yearning for perfect love. He had few friends. His closest acquaintance was another young man of delicate and refined spirits, James Hunter Samson*, who had moved from York to Kingston early in 1819 and with whom he corresponded, though irregularly. They began a debate that year on the merits of love and friendship. Baldwin was adamant: love between a man and woman was nobler than the friendship of two men.

Some of Baldwin’s leisure time went to poetry. He and Samson exchanged their work and offered criticism. In June 1819 Baldwin dropped a planned epic in favour of an “Ode to Tecumse,” which Samson admired. For Baldwin, poetry was an important means of expressing the thoughts and emotions that dominated him. One recurring theme was love – much of the poetry was dedicated to women, individually or collectively. Another theme was virtue. He admired Tecumseh* as one more “Resolved to perish than to yield.” In his early correspondence Baldwin also exhibits a frailty in health that would be his companion through life. His mental health was equally vulnerable. Yet the public world, and probably his own family, knew little of the doubts and demons tormenting young Robert.

His greatest yearning – for perfect love – was satiated early in 1825. He fell in love with his first cousin Augusta Elizabeth Sullivan. Robert’s recently discovered private correspondence with her reveals a man of unsuspected passions, fervidly romantic. Admittance to the bar in April 1825 was secondary to his new-found love. When the families discovered it that same month, Eliza was shunted off to relatives in New York. For Robert, their love was a bittersweet experience. Eliza was the only one to whom he could reveal his innermost longings. In his letters he unfettered his emotions – his pervasive melancholy, his fear of professional failure, and his sense of the fleetingness of happiness. He was to go through life acutely aware of human mutability and its most extreme form, mortality. At last able through his relationship with Eliza to plunge into his unexpressed emotions, he was almost self-absorbed. Eliza became “the sweetest source of my future happiness and the kindest soother of my future disappointments.” Love for Baldwin was not fancy; nor was it simply passion. It was more elevated, pure and spiritual. Small wonder he had a predilection for novels extolling the virtues of domestic life. His favourite was Fanny Burney’s Camilla, a panegyric to domesticity and matrimony.

Baldwin was called to the bar on 20 June 1825; three days later he was presented to the court by his father, treasurer of the Law Society of Upper Canada. The true meaning of the occasion was shared only with Eliza: “When I reflect how much of our happiness depends on my success in my profession . . . I own I almost tremble with anxiety.” Yet, despite his preoccupation with Eliza, during their separation Baldwin gained proficiency in the law. He travelled on circuit, probably throughout the western and central districts of the province, and was “more successful” than he expected. In the late summer of 1825 John Rolph*, who had his own law practice, offered to assist him in his. Robert agreed, presumably to gain experience, and found himself immersed in Rolph’s “causes.” In a case before Judge William Campbell*, Rolph, assisted by Baldwin, opposed James Buchanan Macaulay. Rolph unexpectedly ordered Baldwin to address the jury. Baldwin demurred, but finally rose. “Never was I in a more distressing situation,” he wrote Eliza; all he could think of was “what passed between us” on a night seven months earlier. Then he proceeded, gaining in confidence as he went along. Macaulay spoke highly of Baldwin in his summary; “it was a moment of great happiness,” he told Eliza. A capital case came next and Baldwin won an acquittal. Late in 1825 he finished his first tour of the assizes circuit. His friends judged him a success and, he confided to Eliza, thought a certain speech “affords a prospect of my one day not being altogether undistinguished in my profession – I have a horror of not rising above mediocrity.” Baldwin was “trembling anxious” since “without commanding respect from my profession I never would be worthy of you I never could make you happy.” The brief experience of professional life had been profoundly revealing for the introspective young man. It had, for instance, illuminated his obsession with being right and its concomitant effects upon him – mental anguish and procrastination. In May 1826 he wrote to Eliza: “When a person acts only on their own Judgment they are always fearful of being wrong. . . . Not that I admire indecision on the contrary I dislike it much[.] I know however it is one of my own faults & it pervades more or less everything I do.”

By the end of a year of separation from Eliza, Robert was pleased with his professional progress. One of his clients was a former chief justice, William Dummer Powell*. In May 1826 John Strachan, about to leave for England, called on Baldwin to ask if he wanted his name entered at Lincoln’s Inn. Baldwin declined. Love had overtaken a bachelor’s plan for the future. In due course Eliza returned and with a few close friends and many relatives present, she and Robert were married on 31 May 1827. If their correspondence is an accurate indicator, they attained matrimonial bliss. The law practice thrived. Baldwin often cooperated on cases with his father, with his brother-in-law Robert Baldwin Sullivan and, from 1831, frequently with Rolph. Yet life still had its worries. His health was poor and Eliza suffered from continued sickness during her first pregnancy. He fussed over her incessantly, reminding her that Providence had “ordered that few of those maladies with which your sex are visited at such a period should be dangers – they are however all troublesome & call for a husbands care & a husbands fondness.”

Eliza had an abiding effect on her husband. She was only 15 when their courtship began, and she died before turning 26. Although she was of gentle birth and educated to her station, her early letters are somewhat kittenish; later correspondence displays a greater measure of maturity. What attracted Baldwin was not her appearance, which was plain, but her character and opinions, of which we know little. Still, his expectations could only be met by a rare woman. They read the Bible together, his scepticism giving way to unshakeable faith. He came to believe that the body was but a temporary dispensation and the Christian horizon was eternity. He wanted to be with her “never to part,” even after death. The fear of death was removed, “for guilt alone need make us fear our hereafter.”

Between 1825 and 1828 the administration of Sir Peregrine Maitland came under increasing attack from opposition critics, including William Warren Baldwin and Rolph. Matters came to a head in 1828 and, with personal and professional ties to two leading players, Robert was drawn in. On 17 June, John Walpole Willis* delivered in court an opinion that the Court of King’s Bench was illegally constituted. He was dismissed by the governor and the Executive Council on 26 June, by which time the Baldwins had become involved in a collective protest against the court’s legality and refused to argue before it. The affair prompted the Baldwins, no doubt in collaboration with Rolph and Marshall Spring Bidwell*, to launch the first popular campaign for responsible government in the history of the province.

A general election gave the imbroglio political overtones, especially in York and vicinity. Accepting nomination “in this important and alarming crisis,” Robert ran in the county of York. Late in July the riding was taken by Jesse Ketchum* and William Lyon Mackenzie*, Baldwin coming in last in a four-man race. The election did nothing to put out the fire of protest ignited by the Willis affair. At a meeting on 15 August, at which a petition was adopted which included a plea for responsible government, the Baldwins played leading roles, Robert moving key resolutions. It was, as he put it, a time when colonial policy had become important because of “the misrule of Provincial administrations.” Maitland defended his administration in a dispatch to London; in it he referred to the Baldwins as the only gentlemen associated with the opposition.

On 13 November, Robert was named to the committee to prepare an address to the new lieutenant governor, Sir John Colborne*. Through the fall and winter of 1828–29 Baldwin participated in meetings and committees protesting Willis’s removal, presenting other grievances, and urging the attention of parliament. In a by-election in December 1829, after John Beverley Robinson* had been appointed chief justice and resigned his seat for the town of York, Baldwin defeated James Edward Small*. In his victory speech Baldwin pronounced himself “a whig in principle, and opposed to the present administration.” The writ of election had been improperly issued, however. In a new election Baldwin was opposed, unsuccessfully, by William Botsford Jarvis*. On 30 Jan. 1830 he took his seat in the assembly.

Baldwin was a regular participant in its affairs but not a dominant figure. He chaired several committees and gave evidence before others, including one headed by Mackenzie on the currency. A stockholder of the Bank of Upper Canada, Baldwin took exception to its administration, which he linked to the provincial executive. The following June he led a group of stockholders in an attempt to have an independent director elected to the board. Nominated himself he was defeated by an administration supporter, Samuel Peters Jarvis. With the death of George IV in June 1830, parliament was dissolved and a new general election called. Baldwin was defeated by W. B. Jarvis and dropped from the political scene. In September 1835 Colborne suggested the Baldwins for the Legislative Council if the secretary of state considered it “expedient.” Neither was appointed.

Robert disliked politics. More important, he was preoccupied with his practice and family. He worried about the health of Eliza, increasingly delicate, and the daily routine of his expanding family in their Yonge Street home. The birth of Robert Baldwin Jr on 17 April 1834 by surgical means was a blow to Eliza’s health. In May the following year she journeyed to New York with her father-in-law to recuperate. On the eighth anniversary of their marriage, Baldwin longed to join her but refrained: “it would be inconsistent with duty And I know my Eliza too well not to know that she could never wish me to sacrifice it to inclination.” Eliza returned home but never recovered. She died on 11 Jan. 1836. Baldwin was devastated. His brief happiness had ended almost as he had foreseen it. “I am left to pursue the remainder of my pilgrimage alone – and in the waste that lies before me I can expect to find joy only in the reflected happiness of our darling children, and in looking forward, in humble hope, to that blessed hour which by God’s permission shall forever reunite me to my Eliza.”

What soon happened to Baldwin publicly takes on added meaning in the light of what is now known of his personal life. The new lieutenant governor, Sir Francis Bond Head*, arrived in Toronto on 23 Jan. 1836. Expectations were high among opposition groups that Head would attempt conciliation and reform, as he had been instructed. Maladministration by the Executive Council had been an opposition target since the days of Joseph Willcocks*. By 1828 reform of its administration, by responsible government, had become the issue associated with the Baldwins, father and son. Up to 1836 there were a variety of opinions about the most efficacious means of reform: responsible government was only one. Now the opposition looked to the composition of the council for a sign of Head’s intentions.

The three executive councillors (Peter Robinson*, George Herchmer Markland*, and Joseph Wells) were anxious for new appointments. Head’s first choice was Robert Baldwin, whom he considered “highly respected for his moral character – being moderate in his politics, and possessing the esteem and confidence of all parties.” Robert stated obstacles to Head. First, a council could not support the crown unless it possessed the assembly’s confidence; thus, further appointments would have to be made. Secondly, although Baldwin was “on perfectly good terms” with the present councillors “in private life,” he had “formerly . . . denounced them . . . as politically unworthy of the confidence of the country – and therefore . . . felt that [he] could not take office with them.”

Having consulted his father and Rolph, Baldwin declined a seat. At a second interview he asked that his father, Marshall Spring Bidwell, John Henry Dunn, and especially Rolph, be appointed. Head consulted with Bidwell before again offering Baldwin a seat on the understanding that, if he accepted, Rolph and Dunn would be appointed. In spite of support from his father, Rolph, and Bidwell, Robert refused because Head was unwilling to dismiss the old councillors. When Rolph felt it wrong to continue the negotiations without a concession, Robert gave “a most reluctant consent”; he, Rolph, and Dunn would take office “as a mere experiment” without pressing for the retirement of Robinson, Wells, and Markland. Head agreed to write to Robert indicating that “no preliminary conditions” had been imposed by either side. The new councillors were sworn in on 20 February.

The note, however, was not received until after the ceremony. Head wrote, “I shall rely on your giving me your unbiassed opinion on all subjects, respecting which I may feel it advisable to require it.” This limitation was, according to Baldwin, not in a draft read to him and was unacceptable. On 3 March the council drew up a representation to Head arguing that only responsible government was consistent with the constitution. It was adopted the following day. Head’s reply on 5 March disagreed with the interpretation of the constitution and reminded the councillors they had agreed to avoid important business until familiar with their duties. The councillors convened to consider Head’s reply and on the 12th all six resigned. The assembly, led by Peter Perry, reacted forcefully, treating Head’s action as a violation of the “acknowledged principles of the British constitution.” On 15 April it voted to withhold supplies. The dispute escalated within and without parliament until it was dissolved. By resigning, the council set Upper Canada’s political underbrush on fire.

How responsible was Baldwin, who had been out of politics for more than half a decade and who had just been devastated by his wife’s death? Emotionally and mentally spent, he had accepted office as his duty. Always reluctant to take it lest he be seen as compromising, he was equally ready to resign at the possibility of a taint upon his reputation. A gentleman, a man of propriety, and a political and religious moderate, he constituted an effective symbol for reformers of various political hues, but he was not a gifted organizer. It is impossible now to reconstruct exactly the events between 20 February and 12 March that led to the resignation of the council, but it seems unlikely, as Head and subsequent historians would have it, that Baldwin was the prime mover, capable of winning Robinson, Markland, and Wells to his side. Bidwell, the speaker of the assembly, was undoubtedly one of the two key players in any manoeuvres; the other was Rolph, who had been persuasive enough to get Robert Baldwin to enter the council. Without Baldwin, it is unlikely that Head would have accepted the others. Years later Rolph’s wife claimed: “I Know well that it was not Mr. Baldwin who wrote the remonstrance [3 March] to Sir F. B. Head with respect to Responsible Government”; it was her husband.

Baldwin departed the scene quickly. He left for England on 30 April 1836, bearing letters of introduction from Strachan. He made an unsuccessful attempt to plead for redress at the Colonial Office, then went to Ireland. In England he had mostly been a tourist visiting Windsor, Richmond, and Hampton Court. In Ireland he undertook research into his ancestry. He felt at home in “this dear land of my parents and of my own Eliza and if it makes me a worse philosopher I shall be satisfied if it makes me a better Irishman.” On 10 Feb. 1837 he returned home. Once again he refrained from politics. He had, as Mackenzie asserted years later, no foreknowledge of the rebellion. Still, however, a major figure, he was called upon by Head to carry a flag of truce to the insurgents on 5 December. In the aftermath Baldwin defended several accused rebels, including Thomas David Morrison. In March 1838 Sir George Arthur succeeded Head and two months later the Earl of Durham [Lambton*] became governor-in-chief. The Baldwins had a brief interview with him in 1838 and later submitted detailed comments, principally on responsible government. Despite his resignation and the non-official nature of his report, published early in 1839, Durham’s recommendation of responsible government and union carried enormous force in the Canadas. The certainty of union and the weight attached to an altered role for the Executive Council ensured Baldwin would remain important to reform. That status was enhanced by his reputation as a man of principle. Francis Hincks*, a neighbour, intimate friend, and banker to Baldwin, was now principal strategist of the Upper Canadian reformers and saw the necessity of Baldwin’s leading them and of forming close links with their Lower Canadian counterparts.

Architect of the union was Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson*, later Lord Sydenham. The importance of a new and pragmatic relationship between governor and Executive Council had been set out in the famous dispatch of Colonial Secretary Lord John Russell to Thomson 10 Oct. 1839. Such was its impact that William Warren Baldwin was initially persuaded that responsible government would be established. Russell, in fact, had urged only conciliation and harmony in relations with the assembly. The focal point of this thrust was a reconstituted Executive Council. Thomson, convinced of the value of Robert Baldwin in the realignment of politics in the Canadas, sought him for the new council. Again with extreme reluctance and want of confidence in his colleagues on council, Baldwin accepted, becoming solicitor general in February 1840 but without a seat on council.

When union was proclaimed in February 1841, at which time Baldwin entered council, he faced a dilemma. Reformers were divided over whether he should remain as solicitor general and he himself was ambivalent. He forced the issue of responsibility that month by declaring to Sydenham his “entire want of confidence” in most councillors. Yet he retreated when confronted by Sydenham and accepted his vague commitment to the unclear principles of Russell’s dispatch. The episode confirmed Sydenham’s belief that, as he wrote Arthur, Baldwin was “such an ass!” Sydenham held the upper hand in the general election of March 1841. Although the French party captured nearly half the Lower Canadian seats, corruption and intimidation assured election of pro-government members in Upper Canada. Only six independent or ultra-reformers, including Baldwin, were returned.

Baldwin had withdrawn as a candidate for Toronto when defeat seemed certain but was elected for Hastings and 4th York, choosing to sit for Hastings. The immediate task was to revitalize the party. With French Canadian liberals dispirited and divided over whether to cooperate with Sydenham’s government, Baldwin reconfirmed his commitment. When taking the oaths as an executive councillor in May, he refused the oath of supremacy; denying any foreign prelate had authority in Canada, it denied the rights of the pope and the Roman Catholic Church. An irritated Sydenham agreed to forgo the oath but complained to Russell that Baldwin was “the most crotchety impracticable enthusiast I have ever had to deal with.”

Sydenham and his solicitor general met on 10 June. Baldwin demanded four cabinet posts for French Canadians and warned that on a vote of confidence he would have to oppose the government. Sydenham had had enough. What is usually treated as Baldwin’s resignation was no more than a veiled threat by him during the conversation, but Sydenham used it as an excuse. He wrote on 13 June to accept the resignation Baldwin had not offered. It was a coup which, Sydenham was convinced, would end Baldwin’s career. For some weeks, Baldwin wrote his father, he felt he was not “at all calculated” for politics. But, with the firm support of his family, he determined to fight on for his principles.

Yet there was much to the self-analysis. He was not a natural politician. A poor orator, and a less frequent contributor in parliament than other spokesmen, he even lacked the appearance of a leader. Of above average height, he had a pronounced stoop which made him look shorter, as did the heaviness of his body. His pallid complexion and dull, expressionless eyes gave him a funereal bearing. It was his character which made him outstanding. Baldwin lived the rhetoric of his times: he was a gentleman, morally courageous, utterly genuine in his willingness to sacrifice his interests to those of the institutions he revered – the constitution, the law, the church, property, and the family. His political opinions were essentially Whiggish, which meant a commitment to popular government and individual rights, and an adherence to the values of a landholding class and a social structure rooted in the family and traditional forms of mutual obligation. Other politicians, such as Robert Baldwin Sullivan and Sir Allan Napier MacNab*, who talked of honour knew it might have to take second place to other considerations. They paid deference to a man for whom there were rarely other considerations. To contemporaries as disparate as Wolfred Nelson* and Malcolm Cameron*, Baldwin was known for his honesty, integrity, and disinterested views.

Central to the idea of a gentleman was service. Baldwin’s station in life thrust on him the responsibility to serve and he accepted it, despite his discomfort in office, his intensely private personality, and the disruption of his family life. Baldwin readily admitted he wished to exercise power but he disliked the politics of winning it and would sacrifice neither principle nor party to gain it.

When the first parliament of the Canadas met in Kingston on 14 June 1841, Baldwin faced challenges from a friend. Francis Hincks found Sydenham’s business-like government ever more attractive. By July his Examiner was sympathetic to the ministry, by August he was voting with it on important measures, by Christmas he was urging the reform party to merge with the administration. Dazzled by dreams of economic progress under Sydenham, Hincks rejected Baldwin’s alliance with the “unprogressive” French Canadians. But throughout the session Baldwin himself opposed the expansionist economic programs of Sydenham and Hincks. He and the French Canadians blocked the scheme for a “bank of issue,” intended to provide sound paper money for Canada, and even opposed, unsuccessfully, the British loan guarantee of £1,500,000, intended for canal construction, which had done so much to lure Upper Canada into the union.

Baldwin combined British passion for liberty with insistence upon justice for French Canada, although he thereby endangered his popularity in Upper Canada. The most practical expression of concern was his arranging for the election in 4th York of the French party’s leader, Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*. The least practical was pushing biculturalism to an absolute balance. In August he opposed a popular bill to provide municipal government for Upper Canada because it did not create parallel institutions in Lower Canada. However, Baldwin’s contribution to French–English cooperation was one of his most important legacies to Canadian politics. It was characteristic that he sent all his children to francophone schools in Lower Canada and that he felt acute embarrassment over his own unilingualism.

Baldwin’s major concern, responsible government, was raised several times in the assembly during the session. The most important occasion brought his much mythologized action of 3 Sept. 1841. The standard account says that Baldwin introduced resolutions intended to make the assembly and the ministry define a position on the principle of executive responsibility, and that Samuel Bealey Harrison*, on behalf of the ministry, countered with his own resolutions, which had to embody much of Baldwin’s text to gain a majority. In reality, events were more confused and Baldwin’s ideas less triumphant. He had prepared resolutions as had the ministry. Baldwin was shown the ministerial version and agreed, the cabinet thought, to introduce it in a gesture of constitutional harmony. Through misunderstanding or excessive zeal, however, he broke the agreement. In the house he accepted the thrust of Harrison’s resolutions but insisted on presenting his own, convinced that only his formulation was fully acceptable. In the end, his version was defeated and Harrison’s adopted, Baldwin voting for every one of its resolutions, against predominantly tory opposition. Baldwin had attempted to establish, beyond argument, the practice of responsibility, particularly by insisting on the assembly’s right to hold executive councillors responsible for government action. His precise wording gave way to Harrison’s carefully ambiguous text. It probably did not matter. In years to come reformers would seize on the Harrison resolutions as a sanction and the subtleties would be submerged in politics.

For the moment it appeared Sydenham had again dammed up constitutional protest. That dam was breached when he died on 19 September. With him went his so-called régime of harmony, based on his personal political ability and ruthlessness. Baldwin could not take advantage of the removal of the Sydenham yoke because of the continuing public split with Hincks and the business-minded reformers Hincks represented. Despite public attacks in the Examiner, Baldwin kept lines open to Hincks, even defending him in May 1842 in a libel suit initiated by Archibald McNab. With Sydenham gone, reformers began to wander back into the fold. By the early summer even the tories were listening to Baldwin’s proposals for a temporary alliance to defeat the government.

The new governor, Sir Charles Bagot*, had neither the strength nor the inclination for Sydenham’s ruthless style. Although Hincks became inspector general of public accounts on 9 June, ministerial drift continued. In July, Attorney General William Henry Draper* and Harrison advised Bagot the ministry could not survive: he must bring in the leaders of the French Canadians and that meant inviting Baldwin as well. Draper, who considered Baldwin a traitor for resigning the previous year, was nevertheless prepared to make way for him. Although under instructions from Britain to keep Baldwin and the French out, when the legislature convened in September and it was apparent the reformers had a majority, Bagot had to ignore his instructions and call on La Fontaine. The talks nearly foundered on the governor’s refusal to include Baldwin but he finally conceded. On 16 September, La Fontaine agreed to enter the ministry, with Baldwin.

Although Bagot and Baldwin would eulogize the triumph of responsible government in what Bagot dubbed his “great measure,” the achievement was considerably less. Six previous ministers were joined by five reformers, but there was no prior agreement on policy and no commitment to cabinet solidarity. That they worked as a cabinet, and that Hincks rehabilitated himself as a solid party man, owed more to personalities and politics than principle. In October, Bagot prorogued parliament. Forced to seek re-election with the other new ministers, by virtue of their appointments, Baldwin was defeated by Orange mobs in Hastings and 2nd York. He gratefully accepted a Lower Canadian seat. On 30 Jan. 1843 he was returned by acclamation in Rimouski, forging another link between east and west.

During his first term as attorney general west, (September 1842-November 1843), Baldwin showed his strengths and weaknesses. He was liberal in his leniency towards all but the most hardened criminals and his support of individual rights against arbitrary exercise of police and judicial power. His effectiveness as a law officer was not matched in his role as political manager. Attacked by critics for operating a spoils system and by supporters for leaving too many tories in office, faced by quarrels even within cabinet over appointments, he found patronage “the most painful and disagreeable” of political concerns.

Baldwin valued friendship but found it difficult to reach out to maintain it. Friends, including La Fontaine, commented on his elusiveness and his failure to reply to letters. Most contemporaries ascribed his peculiarities to his “reserve” or to overwork. But by 1843 he was showing symptoms of a severe depressive illness which would worsen as he grew older. By his second term as attorney general, after 1848, he would be incapacitated for extended periods by depressions, unable to represent the crown on the assizes. He claimed the press of political affairs required his presence in Montreal. However, he did not attend some ten meetings of the Executive Council for the first six weeks of the new government. Similar difficulties in business and absences from council marked the last three years of the government, 1849–51. In 1850 he confined himself to home from early January until mid March. The only known visitors outside the family were La Fontaine and Provincial Secretary James Leslie*. The former was shocked by the fluctuations of Baldwin’s disorder, especially the headaches torturing him year after year.

When his government was threatened in 1850 by the radical Clear Grit revolt in its ranks [see Peter Perry], Baldwin’s growing incapacity weakened it further. A friend and party organizer, William Buell*, wrote to him in June that confidence in him was waning; his critics, Buell related, saw him as a spent force, as “the finality man.” It was a suspicion Baldwin himself nurtured. His need to isolate himself was expressed in his frequent desire to resign.

Since his wife’s death in 1836 Baldwin’s obsession with her had deepened into a cult in which she was more real than living people. The anniversaries of her death and their wedding were annual rites. Robert’s father died on 8 Jan. 1844, leaving him grief-stricken, contemplating retirement from politics. For the introspective son, left to carry on his father’s work of achieving responsible government without his father’s flamboyant personality, the heritage was onerous. It heightened Robert’s well-developed sense of family and feeling of responsibility for it. Unfortunately, he could more easily express this responsibility than the affection behind it. His granddaughter, Mary-Jane Ross, described Baldwin as the only source of affection his children knew and yet he was more venerated than loved: he was “a schoolmaster” to them. This man of ancient griefs and loves would have been unrecognizable to the political world, where he was so controlled and reserved. It is a measure of his force of character that he played out his role in politics for so long and so well, carrying the weight of oppression in his own mind. However, the reputation he had won for determination in pursuing responsible government must be balanced by his tendency to retreat through abdication. Duty and his father’s mission prevented him from doing so permanently, but for a few months each year depression brought isolation.

Still, he was a dominating figure in parliament. After Bagot fell ill in November 1842, Baldwin and La Fontaine had a free hand – the first real premiers of the province. In March 1843 a new governor, Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, arrived with instructions to check the “radical” government. He expected confrontation, convinced only the tories were loyal. He saw Baldwin as fanatical and intolerant and, curiously, as one who took pleasure in conflict. Baldwin, in fact, was conciliatory. He allowed Metcalfe an involvement in the working of cabinet and administration that Bagot had never claimed, and urged reformers to avoid criticism of the governor. So unaware was Baldwin of Metcalfe’s motives that he did not press on with the government’s program before the governor could muster support against it.

In May, Baldwin persuaded Metcalfe to withdraw sanctions against his old friend and leader, Marshall Spring Bidwell. He was disappointed that Bidwell did not choose to return to Canada. While Britain was reluctant to grant a general amnesty to those implicated in the rebellions, Metcalfe was permitted to pardon exiles individually. A threat by La Fontaine and other Lower Canadian ministers to resign forced an amnesty for Louis-Joseph Papineau*. Baldwin, in contrast, nursed old grievances and made no direct effort for W. L. Mackenzie.

The reformers began a session on 28 Sept. 1843 which was to be, in many ways, a triumph. Hincks and Baldwin cooperated on legislation strengthening the financial base for Upper Canadian schools and providing for separate schools for religious minorities. A motion was passed demanding control for the assembly over the civil list. And, despite the opposition of some Upper Canadian reformers, the ministry acted to move the capital from Kingston to Montreal. Baldwin, although a landowner, strongly supported Hincks’s bill to tax wild land, and himself drafted a bill to create the non-sectarian University of Toronto. Both bills died when the government resigned in November.

Relations with Metcalfe had, however, deteriorated. Baldwin had moved to control violence by the Orange order, proceeding by the method followed in Britain: a parliamentary address to the crown asking for action against Orangeism. Metcalfe insisted on legislation. After a violent debate, bills were passed restraining party processions and banning secret societies. Baldwin’s family paid a price: on the night of 8 November an Orange mob burned effigies of Baldwin and Hincks outside the Baldwin home in Toronto. Yet, Metcalfe reserved the very legislation, the Secret Societies Bill, he had insisted Baldwin introduce. The bill disappeared into the Colonial Office, to be disallowed in March 1844.

The government might well have resigned over this reservation, but it was patronage that precipitated the crisis. Metcalfe had instructions to control appointments. His practice of that control, without consulting his ministers, made a mockery of responsible government and forced their hands. Following a stormy interview with Metcalfe, Baldwin and La Fontaine met the executive councillors and all but Dominick Daly* resigned on 26 Nov. 1843. There was excited debate in parliament on the 29th, highlighted by Baldwin’s lucid defence of the ministry and responsible government. The house adjourned three days later.

Baldwin clearly understood the resignation to be one of principle, necessary to resolve the constitutional issue. La Fontaine, on the other hand, expected it to force Metcalfe’s recall and the ministry’s return. The following year Hincks was reported as saying “we did not believe our resignation would have been accepted.” Hincks and La Fontaine, it appears, hoped to use the threat of resignation to gain the upper hand on a recalcitrant governor. The election campaign of September 1844 went badly for Baldwin. Metcalfe cried loyalty to the crown: while the French party won a majority in Lower Canada, Baldwin was returned with only 11 followers in Upper Canada. Even Hincks was defeated in Oxford.

Baldwin soon rose from defeat. In the session of 1844–45, he gave the strongest performance of his career. He used debates, whatever the subject, as opportunities to lecture on responsible government. His other major theme was nationalism. Control of the civil list was only partly a constitutional question, it was also a demand that Canadians manage Canadian affairs. His affection for things British took second place to his Canadian nationalism. In March 1846, during a debate on the militia, he insisted it was capable of defending the province without British help: “We want no foreign bayonets here. . . . He loved the Mother Country, but he loved the soil on which he lived better.”

The tory government of William Henry Draper and Denis-Benjamin Viger* was weak, especially after the dying Metcalfe was replaced by the more neutral Lieutenant-General Charles Murray Cathcart, as adminstrator in November 1845 and as governor the following April. But the reform alliance was rickety. Many French Canadians listened to overtures from the tories. With even La Fontaine teetering in 1845, Baldwin could do little but remind his colleagues of the tory record on French Canadian rights. In the end, all negotiations foundered and the reform party remained intact.

Baldwin reduced his private involvements to concentrate on politics. A relative, Lawrence Heyden, was hired in 1845 to manage the extensive family property. This was salutary because Baldwin found it difficult to resist pleas for loans and could be extremely lenient with some debtors. He withdrew from active participation in his law practice by 1848, leaving it largely to his partner Adam Wilson*. The practice had been made difficult by his other partner, cousin Robert Baldwin Sullivan, who was likeable and clever but drunken and irresponsible.

The reformers’ prospects had improved considerably after the arrival of Lord Elgin [Bruce*] as governor in January 1847. He carried instructions endorsing ministerial responsibility and strict neutrality for the governor. The weak tory ministry avoided controversial legislation in the session of 1847, and Baldwin’s major differences were with his allies. He led the successful opposition to William Hamilton Merritt*’s bill to permit the formation of general partnerships with only limited liability, “on the old fashioned principle that men were bound in conscience, and ought to be bound in law to pay all their debts.” He attacked the attempts of modernizers in both parties to reduce the dower rights of women. A bill by Solicitor General John Hillyard Cameron* would have permitted a husband to dispose of property without his wife’s consent. Baldwin contended that “the main object of this Bill was the injury of woman, and to despoil them of the trivial rights they now held.” He ignited the house and defeated it. His concern, however, was primarily with rights of property and the traditional economy which was being revolutionized by corporations, mining companies, and railways. On dower, as on other issues of 1847, he sought to prevent what he called, in debates on primogeniture, “the evil of subdivision of properties.” He was not sympathetic to expansion of women’s legal rights, and in 1849 his government took away the virtually unused right of Upper Canadian women who met the property qualification to vote.

Parliament was prorogued on 28 July 1847 with every expectation of an election. Baldwin chose his issues carefully. The university question, an emotional cause in Upper Canada, was kept at the forefront by a broadly based committee which supported Baldwin’s University Bill of 1843. Baldwin was forced to attend to his own re-election in York North, formerly 4th York, where his campaign was directed by the leader of the Children of Peace, David Willson*, his manager in 1844. His opponent was the editor of the British Colonist, Hugh Scobie, whose manager, tory William Henry Boulton*, waged a scurrilous campaign. Baldwin’s canvass of the riding was successful and he carried the election, which ended in January 1848. The Baldwinites took 23 of Upper Canada’s 42 seats while their allies in Lower Canada captured 33 of 42. It was an overwhelming majority and Baldwin worried whether it could be kept together and reform expectations of immediate and sweeping change could be met. In February he warned the eastern Upper Canadian chieftain, John Sandfield Macdonald*, that if reformers insisted on extreme changes before a proper reorganization of government, they would have to find another leader and would wander in the wilderness until they learned “more practical wisdom.” This gloomy prognosis in victory was characteristic of the depressive Baldwin, but it was also an accurate prediction of the troubles of the reform ministry.

When the house met on 25 February the tories clung to office. Baldwin’s amendment to the reply to the throne speech constituted an expression of non-confidence in the government. It was passed 3 March: 54 to 20. The ministry resigned the next day. La Fontaine was called by Elgin on 10 March and Baldwin and the other ministers were sworn in on 11 March; they held their first cabinet meeting on the 14th. In negotiating the cabinet’s composition with the two leaders, Elgin noted that Baldwin “seemed desirous to yield the first place” to La Fontaine.

Baldwin began with a short housekeeping session. It was a wise strategy, administratively, for it allowed the new ministers to master their departments and sort out the disorder after four years of weak government. Politically, it was a mistake to disappoint the faithful, especially when many would disapprove of the cabinet’s composition. Robert Baldwin Sullivan and René-Édouard Caron*, traitors to many reformers, were included. As bad was the fact that 4 of the 11 new ministers did not secure seats and were thus removed from scrutiny in the house, a curious situation for the first responsible government. Only one member, Malcolm Cameron, came from the radical wing, in a newly invented post with no apparent function, assistant commissioner of public works. Baldwin had done little to meet the party’s expectations and taken long strides towards alienating the radicals.

The times were not auspicious for the new government, which came to be known as the “Great Ministry.” The economic depression dragged on and the provincial accounts were running a deficit. Hincks was again inspector general but despite promises of retrenchment, the deficit grew dramatically in the ministry’s first year. Faced with political reality, the reformers pushed expenditures from £474,000 in 1848 to £635,000 in 1851. The fortuitous return of good times in 1850 with an increase in customs revenue produced a surplus of £207,000 in 1851. The surplus did not satisfy many reform partisans who had a powerful ideological commitment to retrenchment and smaller government. Baldwin’s administration was bedevilled in the house by back-bench revolts over expenditures and warnings from followers that the increase in the size of government was threatening to rupture the party and as one reformer, Daniel Eugene McIntyre, lamented, create “a precious mess.”

Hincks’s ethics were often in doubt; his financial expertise was not. In England in 1849 he persuaded major financial houses to support provincial debentures and railway projects. The results allowed Baldwin and the government to press on with their reforms. Otherwise, Baldwin, who showed little understanding of economic affairs, was not much interested in the fine points of Hincks’s financial dealings. He was also unenthusiastic about the grand financial schemes and retrenchment programs of William Hamilton Merritt who joined the cabinet 15 Sept. 1848. However, one economic issue could unite all reformers – reciprocity with the United States. Some liberals responded to British free trade by becoming doctrinaire free traders and others, notably Robert Baldwin Sullivan, called for Canada to develop a policy of protection, but all could agree on the advantages of freer trade with the United States. Baldwin, essentially pragmatic on tariffs and cool to free trade dogma, could join with the laissez-faire men on the interrelated issues of reciprocity and free navigation. On 18 May 1848 the Executive Council had attacked continuance of the British navigation acts, which limited colonial trade to British ships. In January 1849 Baldwin and Hincks moved an address to the queen for the immediate repeal of the acts. It passed unanimously. The offending acts had by year’s end passed into the history of empire.

The La Fontaine–Baldwin government pursued freer trade with the Maritimes in 1849 and 1850, only to founder on Nova Scotian suspicions. Always reciprocity was the major goal. Baldwin told Elgin in 1848 that he feared for the British connection if it meant Canadian farmers had to accept less for their grain than American counterparts. His solution was an agreement offering the Americans free navigation of the St Lawrence River in return for free trade in natural products. It was a perceptive suggestion, for these were the lines of the reciprocity settlement achieved in 1854, after Baldwin’s retirement. He played a major role in keeping the issue alive, in part through correspondence with reciprocity’s chief protagonist in the American Congress until 1850, Senator John Adams Dix, a relative.

International diplomacy began to be part of Canadian politics as La Fontaine, Sullivan, and Hincks were separately dispatched to Washington between 1848 and 1851 to seek reciprocity, but patronage, closely connected to Baldwin’s conception of responsible cabinet government, loomed larger. Baldwin had always recognized its importance in breaking the tory hold. But, as in 1842–43, he found patronage distasteful and difficult to manage, and by mishandling it he stirred reform discontent. Hincks named a tory, Robert Easton Burns*, a judge without Baldwin’s knowledge. Baldwin himself damaged the party in the Henry John Boulton* case. Once a compact tory, Boulton now claimed to be a loyal reformer. When it was revealed in 1849 Baldwin had promised Boulton a judgeship, the Toronto Globe angrily attacked the would-be judge. Baldwin retreated in January 1850, claiming he had never guaranteed Boulton the job. Boulton soon joined the Clear Grit radicals as a vigorous and troublesome critic of the government.

A lasting legacy of Baldwin’s second term as attorney general was the reform of the Upper Canadian judicial system in 1849. A new Court of Common Pleas and a Court of Error and Appeal were created; the Court of Chancery was reformed and expanded from one to three justices. Hincks later said Baldwin had laid out the basics of the reforms and given them final shape, while Solicitor General William Hume Blake* had helped in the drafting. Baldwin himself, not one to take credit for others’ work, stated that he and Blake had worked together but Blake had drafted the Chancery Bill. Ironically, it was chancery which stirred controversy and helped drive Baldwin from politics in 1851.

Baldwin had to deal with two other difficult issues, the penitentiary question and amnesty. A commission to investigate charges of corruption and brutality at Kingston Penitentiary was dominated by its secretary, Globe publisher George Brown*. The report was lost in excitement over the rebellion losses crisis in April 1849, but its cruel rationalism about prison discipline, adapted from American models, would not have appealed to Baldwin. He delayed legislating about the prison until 1851 and then only improved its administration, thus souring his relations with Brown.

On taking office in 1848, Baldwin insisted Britain must grant a general amnesty for the rebels of 1837–38. Britain acceded in 1849. However, Baldwin was unable to satisfy three prominent exiles. With Robert Fleming Gourlay*, expelled from Upper Canada in 1819, he could not reach an agreement. Marshall Spring Bidwell, despite Baldwin’s promises to establish him in a legal career, seemed unwilling to come back with anything less than a guarantee of political leadership. By 1849 he too was complaining to disaffected reformers of Baldwin’s ingratitude. The complaints were more justified with W. L. Mackenzie. He had had to wait for the general amnesty. His demands for compensation for parliamentary salary and committee expenses owed him from 1837 were dismissed contemptuously by Baldwin, who had a special hostility for Mackenzie the smasher. Baldwin effectively drove him from the party and made him a dangerous, indeed a lethal, enemy.

The La Fontaine–Baldwin government took office amid extraordinary unrest. Economic depression, the Irish famine migration, and revolutions in Europe helped stimulate riots by the Orange and the Green, Toronto tories furious over Mackenzie’s return, angry sailors at Quebec, discontented railway navvies, and thousands more. From 1846 to 1851 rural French Canada saw arson and rioting against attempts to impose a centralized school system on the parishes [see Jean-Baptiste Meilleur*]. The “Great Ministry” is often seen by historians as committed to rapid progress, operating in a society sharing the same values. Clearly large numbers did not share a sanguine view of progress and Baldwin himself was racked with doubts. It was a time of transition and the movement from a traditional to a capitalist economy was not accomplished without opposition, often violent.

The most serious threat to the government arose from the rebellion losses crisis of 1849, when tory fury was directed against alleged French domination of the province and especially against La Fontaine. Baldwin took little part in the debate, fuelling opposition speculation that he did not support the government’s proposal. Indeed, he seems to have had doubts about compensation for those convicted of treason and only assumed leadership when the legislation was amended to exclude convicted rebels. Taking a hard line with the opposition, he kept the house in session through the night of 22–23 February until the resolution was passed.

During the riots in Montreal after the signing of the bill by Lord Elgin on 25 April, Baldwin’s boarding-house was attacked by a mob, but there is no indication he was within. He was a member of the Executive Council committee which took responsibility for policing the city and made the potentially disastrous decision to swear in French Canadians as constables and arm them. Only a promise to withdraw these constables placated the tory mob and prevented a blood-bath. Baldwin moved quickly on the political front, urging reformers in Upper Canada to mount pro-government rallies and petitions, and personally financing petition campaigns in rural Upper Canada. He was instrumental in the cabinet’s decision to move the capital from Montreal to Toronto in October 1849.

When the disgruntled tories turned to annexation to the United States as the solution to Canada’s problems [see George Moffatt*], Baldwin with ruthless efficiency weeded annexationists out of public offices. He was equally firm with the reform party. Peter Perry, suspected of being an annexationist, was the candidate for the radical reformers in a by-election for York East to take place in December. Baldwin quickly set him straight. On 4 October, in a letter widely published in the reform press, he warned Perry “all should know therefore that I can look upon those only who are for the Continuance of that [British] Connexion as political friends, – those who are against it as political opponents.” Perry publicly pledged not to discuss annexation and the party was steadied.

The crisis of 1849 helped obscure the government’s continuing accomplishments. Just as surely has the achievement of responsible government, confirmed when Elgin signed the Rebellion Losses Bill, diverted attention. Baldwin was seen, by the Examiner and others since, as the man of one idea who had little to offer once responsibility was gained. In fact, the government, and Baldwin in particular, had a lengthy list of important reforms.

The Municipal Corporations Act provided the efficient system of local government reformers had been crying for since Durham had emphasized the need in his report. The act replaced the unwieldy districts with counties and allowed for incorporation of villages, towns, and cities, with each receiving an elected council (as did the townships). The act has been seen by some historians as a grand extension of democracy and as Baldwin’s creation. By providing elected councils, it gave the municipalities a measure of independence from provincial control. However, it retained three restrictions: division of financial authority between provincially appointed magistrates and county councils, a property qualification for municipal voters, and appointment by the province of key county officials, including the registrar, sheriff, and coroner. Attacked in the house in 1850 by Peter Perry over these undemocratic remnants, Baldwin, unrepentant, argued the crown’s prerogative was of the essence of a monarchical system, and officers in the administration of justice must be appointed by the crown. He also argued qualifications for voters and office holders were necessary. Hincks should share some credit for the act. A memorandum of December 1848 called for stronger municipalities with taxing and borrowing powers, and his concerns were embodied in the act, which permitted councils to issue debentures. When Baldwin and Hincks clashed in 1851 over railway financing by local governments, Hincks pointed to the act for authority. Baldwin seemed unaware of these provisions, which suggests he did not draft the act alone.

The University of Toronto was unarguably Baldwin’s creation. His October 1843 bill on the university question died with the government in December [see John Strachan]. Baldwin was determined to settle the issue, to end the connection of church and state in higher education, and to destroy King’s College as a visible symbol of Anglican privilege and class favouritism. Soon after taking office in 1848 he had asserted government control. In July he established a commission of inquiry into the finances of the college, which was supported by public lands. Controlled by reformers, the commission documented financial mismanagement and the need for reform. These findings laid the base for the University Bill of 1849, which Baldwin introduced on 3 April. His measure stripped the Church of England of its power in higher education and eliminated denominationalism at the university. To be called the University of Toronto, it would be secular, centralized, government controlled. The denominational colleges in Upper Canada, Methodist Victoria, Presbyterian Queen’s, Roman Catholic Regiopolis and Bytown (University of Ottawa), could affiliate, but would lose the right to confer degrees, except in divinity, and have no share of the endowment. Baldwin did not accomplish all he had hoped. The denominational colleges did not give up their independence and indeed, over Baldwin’s opposition, Bishop Strachan obtained a charter for an Anglican college, Trinity. Still, Baldwin had presaged the pattern of development for higher education in Ontario.

Baldwin also contended with his church over the clergy reserves. His efforts were hampered by reluctance among French Canadian liberals, including La Fontaine, who feared that if Upper Canadian radicals were encouraged by abolition of the reserves, they would attack the religious institutions of Lower Canada. Nevertheless, under pressure from his left wing, Baldwin tried a compromise. On 18 June 1850 James Hervey Price* introduced 31 resolutions in the assembly, the key one asking Britain to give the Canadian parliament power to dispose of clergy reserves revenue. This compromise, at best a modest advance, was adopted but, with the Anglican hierarchy opposed, the British government took no action.

The pressure to settle the reserves question, like the annexation controversy, pointed to one of the most serious threats to the Baldwin government, the increasing impatience of the radical wing. Buoyed by Perry’s election, the Clear Grits adopted a separate platform in March 1850 far in advance of Baldwinite reform in espousal of democracy and voluntarism. The seriousness of the challenge was indicated by the desertion to the Clear Grits of the Examiner, now published by James Lesslie*. During the 1850 session, they behaved more as members of the opposition than as critics within the party.

Baldwin showed neither sympathy for nor understanding of the new liberalism. Indeed, through his mistakes, he fostered it. The token radical in the cabinet, Malcolm Cameron, was assigned in the spring of 1849 to draft amendments to the Common Schools Act of 1841. It was a typical case of Baldwin’s preoccupation with private torments and great public issues while details of political success were forgotten. Baldwin allowed the bill to be introduced without reading it, so he was unaware Cameron was proposing a radical restructuring of the Upper Canadian school system. It passed the assembly in May 1849. Its democratic and decentralizing provisions outraged Egerton Ryerson*, superintendent of schools, who threatened to resign. Baldwin capitulated, though it involved the humiliation of suspending his own government’s act. The inevitable result was the resignation on 1 December of Cameron, who became another rallying point for left-wing discontent. He soon campaigned vigorously for Caleb Hopkins*, a Clear Grit, against John Wetenhall, who had replaced him on the Executive Council. Baldwin, suffering from depression, was disconsolate at Wetenhall’s defeat and resulting insanity, and was widely rumoured to be ready to resign.

The last year of the La Fontaine–Baldwin government was an extended retreat under continual harassment by critics to the left. The extremism released by the rebellion losses and annexation crises and Baldwin’s loss of authority had weakened moderation in politics. The long commercial depression ending in 1850 had increased the attractiveness of economic success in the United States, not only to the Clear Grits but to the tories as well. To Baldwin’s dismay, discussion of such constitutional change as fixed times for meetings of parliament and for elections occurred during the session of 1850. These were, to Baldwin, “part of a plan to change, bit by bit, our present constitution.” He beat back each initiative, but there were always new ones.

Constitutional change was also winning advocates within Baldwin’s cabinet. He had long opposed one panacea, an elected Legislative Council, as an innovation which would destroy the British connection. He was shocked when his cabinet determined it should be given to the radicals as a sop. On 10 April 1850 he wrote to Elgin to tender his resignation: he had no alternative but to leave a government committed to so disastrous a policy. His quiet terrorism worked and there was no more talk of the obnoxious reform from the cabinet. However, he heard a good deal from the house. On 3 June 1850 Henry John Boulton and Louis-Joseph Papineau initiated a debate on constitutional change, including an elected council. With a bizarre twist of opportunism, tories such as Henry Sherwood expressed interest. Baldwin struck back. The innovators were republicans, advocates of independence from a generous mother, guilty of “black ingratitude.” He prevailed and the Boulton–Papineau motion failed, but he had had to threaten resignation, and his defences of the constitutional status quo in the house were becoming shriller.

The opposition also hounded Baldwin on retrenchment, the means favoured by free traders and liberals to achieve smaller government. Its attacks gained force after 21 Dec. 1850, when the popular William Hamilton Merritt resigned from the cabinet, angry that the government would not adopt his sweeping reductions. The rebels found another cause in anti-Catholicism, stimulated by a wave of religious prejudice in England in 1850–51. The chief reform newspaper, the Globe, led the crusade. Its alienation from Baldwin, who was considered too closely allied to French Catholics, was completed in April 1851 when George Brown lost a by-election in Haldimand to W. L. Mackenzie, a defeat Brown ascribed to Catholic votes and lack of support from Baldwin.

An element in Baldwin’s decline was continued conflict with Hincks over economic policy, and the increasing influence of his inspector general. The lines of division were as they had been in the 1840s, given greater point by the emergence of the railway. Although in April 1849 Baldwin supported Hincks’s Railway Guarantee Act, he was suspicious of over rapid development and the financial probity of some companies. That month he unsuccessfully opposed the incorporation of the Toronto, Simcoe and Huron Union Rail-Road, whose money-raising plans sounded to him like “a lottery scheme” [see Frederick Chase Capreol*]. The following year he was alarmed by legislation to permit municipalities to acquire stock in the Great Western but failed to convince the house of the dangers. Hincks moved an amendment to permit municipalities to invest in all railways, not just the Great Western. In the vote, Baldwin found himself in a minority of eight, with six French Canadians and an English liberal from Lower Canada. It seemed he was back where he had begun in 1841, a lonely voice in a house of modernizers.

Hincks was never reluctant to express his differences. In October 1849, angered by disagreements over patronage and crown lands, and by what he perceived as softness towards annexationists, he told Baldwin the country was disgusted with the ministry’s “vacillating policy” and with “you in particular.” Baldwin’s slowness in making cabinet changes led Hincks to snarl, “I could myself complete the administration on a permanent and satisfactory footing in 24 hours.” A clear break did not come until 1851, when Hincks proposed in cabinet an extension of the powers of municipalities to support railways. Baldwin had fought it for months in council. On 30 April, Hincks, certain he had a cabinet majority behind him, wrote to La Fontaine to complain about Baldwin’s obstruction and said he was prepared to resign. Baldwin, who also had been threatening resignation, had to back down. Saving face, he insisted to La Fontaine he was not “concurring” in the proposals, he was simply “acquiescing” in them.

The traditional economy based on landed property, whose values Baldwin adhered to, was being superseded by a capitalist economy. The constitution, which he thought he had settled by responsible government, was under increasing attack. The reform party, his instrument for achieving constitutional purity and French-English unity, was splintering. Religious tensions were transformed into an Upper Canadian outcry over “French domination” within the Province of Canada, and anti-French feeling had become a potent force as the clergy reserves question remained unresolved and Brown’s Globe set itself up as the Protestant critic. The basics of Baldwin liberalism seemed to be losing their constituency.

Robert’s mother had died in January 1851. Personal and political disappointment produced the usual response. Baldwin lapsed into depression, and was seriously ill in May and June. Continued radical harassment drove him deeper within himself. His class, landed proprietors and professional men, was being rejected by capitalist modernizers and radical agrarians. The greed of lawyers and the elaborate legal system became the focus of discontent. J. Reed, a reformer from Sharon, in Baldwin’s own riding, wrote to W. L. Mackenzie in May 1851: “The watchword is to be no lawyers, more farmers and machinists.” The assault gained strength in the 1851 session. Baldwin’s mood was not lightened when, on 26 June, Mackenzie moved for a special committee to draft a bill for abolishing the Court of Chancery and conferring equity jurisdiction on the courts of common law. Baldwin pleaded with the house to give the judicial reforms a chance to prove their value. The house was not listening. Even the solicitor general west, John Sandfield Macdonald, confessed the courts were too expensive and complicated. Mackenzie’s motion was lost 30 to 34. But a majority of Upper Canadians had voted for it, 25 against 8 opposed.

The next day Baldwin wrote to La Fontaine that, after analysing the vote, he had concluded “the public interests will be best promoted by my retirement.” On 30 June he rose in the house to announce his resignation. He explained the vote had left him no choice. In a house where a major reform was given only two years’ trial, he felt himself “an intruder.” Although he had been urged by his colleagues to reconsider, he felt he could be of more aid to them out of office. His emotionally charged address isolated the main theme of his concern: “the consequences of that reckless disregard of first principles which if left unchecked can lead but to widespread social disorganization with all its fearful consequences.” Saying a final word of thanks to the Lower Canadian liberals for their support, Baldwin took his seat with tears running down his face.

The same day La Fontaine announced that he, too, would leave. Hincks could now create a new and peculiar alliance, joining his modernizing reformers with the Grits and with the French party under Augustin-Norbert Morin*. Baldwin watched with discomfort. As a party man he felt that he owed Hincks help, but in September he urged his son-in-law, John Ross*, to avoid taking office in the new ministry if he could. Yet Baldwin himself could not avoid the call of duty. He ran in York North in the ensuing general election. It was a disastrous decision. The Grits nominated Joseph Hartman, who recruited Mackenzie to campaign for him. The old rebel dogged Baldwin’s heels, following him from meeting to meeting to refute his every claim. Baldwin received only a third as many votes as Hartman. Never an effective organizer at the constituency level, as R. B. Sullivan had observed as early as 1828, Baldwin now had lost touch altogether with local interests. His failure to recognize that a coalition with traditional agrarian interests had been possible allowed the triumph of their common enemy, the modernizing reformers. Baldwin nevertheless remained an important political symbol, a subject of excited rumour whenever political liberalism was in difficulty. Such a rumour in 1853 had him returning to lead the shaky Hincks–Morin government. In 1854 Baldwin broke his political silence to urge support of Hincks’s coalition with Augustin-Norbert Morin, which, he said, although far from perfect, deserved public sympathy. In 1856 Auditor John Langton*, viewing the tottering ministry of Sir Allan Napier MacNab and Morin, saw Baldwin as the only alternative to John A. Macdonald* in reconstructing the government. As late as the summer of 1858 reformers were appealing to him to save the party. Even after his death some moderate reformers, including those led by John Sandfield Macdonald, used the name Baldwinites to distinguish themselves from Brown’s more radical supporters. In 1871, in another twist, Brown resurrected the Baldwin tradition and name in urging Catholics to join the Grits in the “reunion of the old Reform Party.”

Baldwin’s relationship with Hincks was not always friendly. A major issue was the University of Toronto. In September 1852 Hincks proposed the abolition of its convocation, which shared government with its senate, and its medical faculty, leaving medical education to private schools such as that founded by Hincks’s ally John Rolph. As well, the senate would include representatives from the unaffiliated colleges, who could obstruct the smooth functioning of the university. It was at this time, on 25 November, that the convocation elected Baldwin chancellor. To accept, he wrote to Professor Henry Holmes Croft*, “would imply less hostility than I entertain to the course adopted by the present Government.” His rejection was also motivated by his need to isolate himself. He refused all offers to remain in public life, rejecting judgeships twice, as well as places on commissions and requests to stand for electoral nominations. He narrowed his life to its basics: home, family, and memories. Only the Law Society of Upper Canada, the law as institution, could draw him out. He served as treasurer of the society from 1850 until his death and as its representative on the senate of the University of Toronto 1853–56. The other partial exception was the Church of England. He had become, he told John Ross in December 1853, “rather a High Churchman as I understand the distinction between High and Low Churchman, though I trust without bigotry or intolerance.” His concern was with maintaining the traditional internal government of the church, in contrast to his pragmatic views on its separation from the state, a reform he had argued was necessary to prevent it from becoming a political football. He did not approve of any democratization of the church. He worked with both high and low churchmen as president of the Upper Canada Bible Society until 1856.

A few honours came his way. On 3 April 1853 the Canadian Institute at Toronto publicly recognized his role as one of its founders. In 1854 he was made a cb. For the most part, however, his was a private existence. He took an interest in improving the property at Spadina, the family homestead, to which he had moved in 1850 or 1851. In summer the garden was a major preoccupation, in winter his past correspondence and the transcribing of his wife’s letters filled the hours as he looked out over the family cemetery. To outsiders he was a ghostly figure, only occasionally venturing out into the streets or receiving friends.

After his retirement his health had grown worse. Debilitating illnesses, real and psychological, tortured him. He had temporary problems with motor control and visual perception, shown by shaky handwriting, misspelling, and repetition of words. Depression remains the most likely diagnosis. His reserve deepened into alienation and self-isolation. The most striking evidence of his deterioration was the letter he wrote to La Fontaine on 21 Sept. 1853, refusing his invitation to join him and his wife on an expedition to Europe. He had been ill since May, “seldom free for two consecutive days from the disagreeable rumbling noise in my head.” He felt giddy, easily worried, and excited. His fear of travel had been fuelled by the death of Barbara Sullivan, his aunt and mother-in-law, who had expired with no warning in 1853. He had a curious preoccupation with his body. As he told La Fontaine, “My organs are too powerful . . . I manufacture blood and fat too rapidly.” This preoccupation contributed to his obsessive thoughts of death. Its nearness had been with him at least since 1826 and especially after Eliza died. The man who had co-ruled Canada was now reduced to pathos, living, his daughter Eliza said, “in dread of another attack.” The family gathered round the invalid; taking care of the great man was a shared burden. Since he refused to leave Spadina, Eliza and John Ross had to move from Belleville to Toronto. The greatest weight, however, fell on the elder daughter, Maria – housekeeper, entertainer, and adviser to her father. To ensure she remained at home, he refused his permission when the scion of a compact tory family, Jonas Jones Jr, and an American professor both wished to marry her. Her father’s prohibitive demands left Maria an embittered and unhappy spinster.

Baldwin’s other daughter had a happier fate. Eliza was married to the much older Ross at Spadina on 4 Feb. 1851. Some of the family were dismayed but Baldwin liked Ross, had sponsored his legal career, and, perhaps, recalled family disapproval of his own romance with another Eliza. Baldwin’s boys were less successful. The elder, William Willcocks, married in 1854 Elizabeth MacDougall, to whom Robert was devoted, but she died in 1855. According to his younger daughter, her death “seems to have broken him down completely . . . he says to him it is like a second widowhood.” Willcocks remarried in 1856 but he was unsuccessful in his career and, probably because of his father’s memory, in 1864 he was given a sinecure at Osgoode Hall. His fiscal irresponsibility forced him to sell his father’s beloved Spadina in 1866. The other son, Robert, a young adventurer who went to sea in 1849, was stricken with polio in 1858 and had to live at home, crippled.

By the summer of 1858 there was little left for Baldwin but his dead Eliza. Headaches had become constant and when he could sleep he was tormented by “harassing and perplexing dreams.” His memory was so unreliable he could not do his law society business at Osgoode Hall. His agony was increased by a last, ill-considered venture into politics in 1858. On the urging of George Brown, now leader of the party, Baldwin agreed to stand for the York divisional seat in the newly elective Legislative Council. It was a nice irony, given that he once had preferred leaving politics to seeing the council become elective. He soon realized he was unfit, physically and psychologically, for public office and on 12 August withdrew.

The family would trouble his last days. By early December 1858 it was clear he was dying, suffering from what the Globe described as “neuralgia in the chest” which had become “a severe case of inflammation of the lungs.” He tried for several days to make his will, tormented by his son Willcocks, who believed incorrectly that Lawrence Heyden was conspiring to have Baldwin reduce his share of the estate. The will, completed on 9 December, distributed the proceeds of a prosperous law practice and the inherited family properties, both commercial and agrarian, in Toronto and throughout the province. They had made him one of the wealthiest men in Upper Canada. The same afternoon, Baldwin died at Spadina. One of the largest funeral crowds in the history of the province came to honour the dead statesman on 13 December. Baldwin was laid to rest. Or so the mourners thought.

The obsession of Baldwin’s later years was his lost wife. His nostalgic love, grief, and guilt that Eliza had died as a result of childbirth were codified in a bizarre document designed to ensure that he would be reunited with her. The nine requests included that certain of her possessions and her letters be buried with him and their coffins be chained together. Most important, he asked that his body be operated on: “Let an incision be made into the cavity of the abdomen extending through the two upper thirds of the linea alba.” It was the same Caesarean section as Eliza had suffered.

The instructions were left with the faithful Maria. She saw to most of them but, perhaps in a last act of rebellion, did not have the operation performed and apparently told no one in the family of the request. A month after Robert’s death, when Willcocks was sorting his father’s clothes, he found in a pocket an abbreviated version, carried there in case Robert died away from home. The old man pleaded with whoever found the note that “for the love of God, as an act of Christian charity, and by the solemn recollection that they may one day have themselves a dying request to make to others, they will not . . . permit my being inclosed in my coffin before the performance of this last solemn injunction.” Willcocks heeded this injunction. One bitter January day in 1859, Dr James Henry Richardson, Lawrence Heyden, William Augustus Baldwin (Robert’s brother), and Willcocks entered the vault and obeyed his request. It was a suitably strange end for one whose public persona and private agony were the sum of a man few understood, few loved, but all honoured.

By his own standards he was a failure. Compelled into politics by a profound sense of Christian duty, he had striven to preserve the rule of gentlemen and all it entailed. By the time he was driven out of politics, what he stood for had been eclipsed by the march of progress and the rise of the men of capital and machines. His accomplishments, none the less, were legion, most important among them the genius of responsible government and the centrally important heritage of a bicultural nation. That he did so much, at such personal cost, was the real measure of the man. It was fortunate that Robert Baldwin had his Eliza, in life and in death, the one immutable element in a world of puzzling change.

[The authors gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of J. P. B. Ross and Simon Scott, who allowed access to their hitherto unused papers. References to Robert Baldwin may be found in almost all the private manuscripts and government collections of the period. The most important sources are the various collections of Baldwin papers at the MTL; and the Baldwin papers (MS 88), attorney general’s records (RG 4, A-1), and Mackenzie–Lindsey papers (MS 516) at the AO. The Coll. La Fontaine in BNQ, Dép. des mss, mss-101 (copies in PAC, MG 24, B14), and the recently acquired Baldwin–Ross papers at the PAC (MG 24, B11, vols.9–10) are indispensible, as is the private collection of Ross–Baldwin papers belonging to Simon Scott.