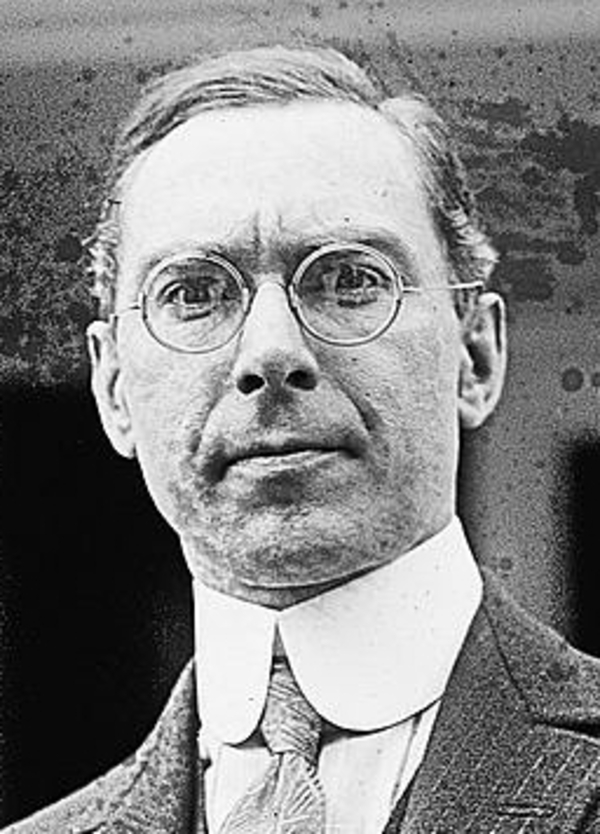

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SQUIRES, Sir RICHARD ANDERSON, lawyer, newspaper publisher, and politician; b. 18 Jan. 1880 in Harbour Grace, Nfld, only child of Alexander Squires and Sidney Jane Anderson; m. 17 June 1905 Helena Emiline Strong (d. 1959) at Little Bay Islands, Nfld, and they had seven children, of whom three sons and two daughters survived to adulthood; d. 26 March 1940 in St John’s.

Possibly Newfoundland’s most controversial political leader, Richard Anderson Squires was the son of a reasonably prosperous (and politically active) farmer-turned-grocer. His mother died when he was very young, his father did not remarry, and Anderson, as he was known to his family, had a solitary childhood. He was educated in Harbour Grace and at the Methodist Academy in Carbonear before attending the Methodist College in St John’s. He later described his time there as “one of grind” since he had to make up for the deficiencies of his elementary education, but he emerged in 1898 with the Jubilee Scholarship, then the colony’s highest academic award. He termed it “pre-eminently an outport boy’s scholarship” and he used it to attend Dalhousie law school in Halifax, graduating with an llb in 1902. A young man of intelligence, energy, and promise, Squires returned home, enrolled as a solicitor, and joined the law firm of the minister of justice, Edward Patrick Morris; he became a partner in 1904.

In 1908 he stood as a candidate in Trinity Bay for Morris’s newly minted People’s Party. He lost narrowly, but won a seat in the same constituency the next year, when the Liberals led by Sir Robert Bond* were defeated. A loyal but not a vocal backbencher during Morris’s first administration, Squires established his own law firm in 1910, and was called to the bar the next year.

In 1913 the People’s Party faced a serious challenge from William Ford Coaker’s Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland, which was in alliance with Bond’s Liberals. Squires had a difficult task in trying to hold Trinity Bay since the FPU was influential there. He lost his seat, but his vigorous campaign had tied Coaker down, contained the spread of unionism, and allowed Morris to devote his attention to crucial seats in Conception Bay. The People’s Party won the election and Squires had his reward. In March 1914 he was appointed to the Legislative Council and became minister of justice and attorney general. In the same year he was named a kc.

For all that he was marked as a coming politician, Squires did not play an especially prominent role during his first few years in cabinet, though as minister of justice he was responsible for imposing Prohibition in 1917. (He was not a teetotaller, unlike many of his fellow Methodists.) Nevertheless, he was intensely ambitious, as was indicated by his 1916 acquisition of a controlling interest in the Daily Star (St John’s). When Morris formed a national coalition government in July 1917, Squires became colonial secretary and leader for the government in the Legislative Council. In this capacity he had to steer a controversial bill imposing a business-profits tax aimed at checking profiteering and ensuring that all sections of the population contributed to the effort demanded by World War I. His eloquence did not prevent its defeat in council, and the government had to appoint additional members to get the bill through.

At the beginning of 1918 Morris resigned. Squires refused to serve in a restructured national government headed by Liberal William Frederick Lloyd, arguing that the government was not truly national, but dominated by Coaker and the FPU. It was, he said, “a political combination of expediency and self-interest.” Squires was, of course, declaring political independence (as Morris had done in 1907), and he had not forgotten that Lloyd had defeated him in the 1913 election.

The common denominators linking those against the Lloyd government were opposition to the FPU and personal ambition. Both influenced two key pieces of legislation. Squires and others resisted a bill that further extended the term of the legislature (Morris had introduced the first such bill in 1917), though they eventually agreed to a compromise. The other bill imposed conscription, which was unwelcome to most FPU members. Squires sought to embarrass Coaker and the government in the legislature, and used his newspaper to force the administration to implement the measure in the spring rather than delay until after the fishing season. Attacks on the government in the Daily Star reached such a pitch that the administration invoked the War Measures Act in May 1918 and closed it down (it reopened on 10 June following the appointment of government censors).

On 20 May 1919 the government was defeated on a motion of no-confidence – seconded, remarkably, by Lloyd himself. A new administration was formed by Sir Michael Patrick Cashin*, and an election was scheduled for the fall. The manoeuvring that had created two national governments had eroded the pre-1917 party structure; political warlords with various degrees of influence and support now jostled for advantage and alliance. Squires made no attempt to reconcile with his former People’s Party colleagues. Instead, once it was clear that neither Lloyd nor Bond would return to public life, he seized the opportunity to take over the remnants of the old Liberal Party and, following Morris’s example once again, absorbed it into a new grouping. The Liberal Reform Party was launched on 21 August, and Squires anointed leader. At this stage it looked as if three parties, led by Squires, Cashin, and Coaker, would contest the election, but Squires wanted to head a majority government. The only way to dislodge Cashin, who seemed assured of victory, was to come to terms with Coaker, at whom Squires had levelled vituperative attacks in the Legislative Council and in his newspaper (they had been amply returned). Coaker, intent on regulating the fishing industry, had his own reasons for joining Squires, and the alliance was concluded in September. Rocky as it proved to be, the partnership defined the primary political fault line in 1920s Newfoundland. On one side were the Liberal and FPU factions, broadly populist, largely outport based, and predominantly Protestant; on the other were the conservative St John’s mercantile factions, far more representative of the country’s elites, and holding most of the Roman Catholic districts.

Not surprisingly, the election campaign had a distinctly sectarian tinge. Squires had served as grand master of Newfoundland’s Loyal Orange Lodge from 1913 to 1915 (and would do so again in 1925–26), and Coaker’s following was almost exclusively Protestant. Cashin’s strength was in St John’s and the southeast, where the greater part of the Catholic population was concentrated. Squires and Coaker had 23 seats to Cashin’s 13, most of them in Protestant districts. Squires was not above using sectarianism to political advantage, but he was no bigot. Indeed, he once caused controversy by taking a group of visiting Orangemen to the annual garden party at Mount Cashel, a Catholic orphanage. Wanting to demonstrate that his party support crossed religious lines, he ran successfully in St John’s West, a district with a Catholic plurality, instead of Trinity Bay. Sectarianism alone, then, does not explain the election result. Coaker and Squires were an effective electoral combination; the party manifesto promised reduced taxes for fishermen, a reorganization of the fisheries department, and industrial development, and ferociously attacked the unpopular Reid Newfoundland Company [see Sir William Duff Reid*], which owned the island’s railways and coastal steamers and had once bankrolled Morris and the People’s Party. Squires also brought a number of personal advantages to the contest: he was clever, charming, witty, and a superb speaker. Yet the election results tended to reinforce sectarian divisions since the government members were all Protestants while 11 of the 13 opposition members were Catholics.

The new administration, in which Squires was colonial secretary as well as prime minister, took office on 17 Nov. 1919. It inherited from the war a heavy public debt and an overextended fishing industry, and it faced a post-war recession. Over the next four years, the total value of Newfoundland’s exports declined by almost 40 per cent, and the price of fish by 46 per cent. Government revenues fell and expenditures increased, pushed in part by the need to provide relief and employment. By 1923 the debt was $60.5 million. The government’s ability to deal effectively with this dismal situation was compromised by friction between Squires, Coaker, the minister of marine and fisheries, and William Robertson Warren, the minister of justice. The political atmosphere was rancorous and highly personal. Governor Sir Charles Alexander Harris reported that as a result of Squires’s vituperative and insulting language – and that of his newspaper – the opposition regarded him with “a bitter feeling akin to hatred.” The sentiment was heartily returned, and legislative sessions degenerated into lengthy slanging matches.

A major issue demanding the government’s immediate attention was a crisis caused by falling prices for fish and international market difficulties. Coaker imposed controls on exports and pushed through other legislation to improve quality and marketing, all measures long advocated by the FPU. But he wanted a greater degree of government intervention than Squires was prepared to tolerate. The prime minister insisted that the regulations had to be implemented by the industry, not the government. Faced with tight finances and heavy competition, exporters soon panicked. That Coaker’s plan had failed by 1921 was due in part to Squires’s strategy, but he could blame the exporters, who could in turn blame Coaker.

The recession also reduced demand for iron ore, creating difficulties for the mining companies working on Bell Island. Any closure or reduction in output had serious implications for the Conception Bay economy. The companies, merged as the British Empire Steel Corporation in 1922, wanted to cut production; Squires wanted as much employment as possible. There were protracted, unsavoury, and secretive negotiations, during which the companies were persuaded to keep working in return for financial concessions. There were generous donations to Liberal campaign funds (and to Squires) during discussions on a permanent contract to replace the one that had expired in 1919.

The government also had to address the future of the dilapidated, loss-making Newfoundland Railway. The Reid Newfoundland Company wished to shed its responsibility for operating the railway and coastal steamers and concentrate on developing its extensive landholdings. In particular, there were plans for a second pulp and paper mill in the Humber River valley. In June 1920 the Reids announced that they could no longer function without government help, thus breaching the 50-year contract signed in 1901 [see Sir Robert Gillespie Reid*]. Over the prime minister’s objections, assistance was provided – thereby driving up the debt – and what Squires described as the “mock railway with nobody to run it” carried on while the government covered most of its operating deficits. A final settlement was forced by negotiations concerning the Humber development. Hostile to the Reids, Squires was initially unenthusiastic about the project; he was also reluctant to allow the government to become the sole guarantor of the bonds needed to raise capital. In 1922 he acquiesced in a deal whereby the bonds would be guaranteed by both the Newfoundland and British governments. His administration agreed to abandon litigation against the Reid company for breach of contract, since this would make uncertain the tenure of the forest-lands on which the future mill depended. In addition, the government bought out the Reid interest in the railway and, on 1 July 1923, would become responsible for its services. These actions were a sensible if expensive solution to a difficult problem, and Squires could trumpet his administration’s role as midwife to the Humber project, which promised to create hundreds of jobs.

There were other positive accomplishments. One of the prime minister’s first acts, in 1920, created the Department of Education under Arthur Barnes* – which rattled the Roman Catholic hierarchy, concerned about its schools – and he provided for a non-denominational normal school which began classes in the autumn of 1921 and would become Memorial University College (later Memorial University of Newfoundland). Impressive national war memorials were begun in St John’s [see Gerald Joseph Whitty*] and in France, including the famous caribou monument at Beaumont-Hamel (Beaumont). Squires did his best for Newfoundland in fish-tariff negotiations with the United States and Spain, and in talks with fish buyers in Italy. On other issues he was evasive: he opposed women’s suffrage in private but not in public (in 1930 his wife would become the first woman elected to the House of Assembly, where she replaced the late George Frederick Arthur Grimes*), and avoided decisive action on enforcing or easing Prohibition which, as elsewhere, encouraged hypocrisy, graft, and petty corruption. He was secretive and suspicious of most of his colleagues, and spent long periods abroad (he was absent for 16 of the 41 months of his first term of office). At home, the government was increasingly fractious.

Nevertheless, the Humber deal gave Squires a superb issue for an election, and he called one for 3 May 1923, promising he would put the “Hum on the Humber.” There was a fierce fight in St John’s West, where Cashin came within a few votes of knocking Squires out of his seat, but overall party standings were unchanged, and the necessary legislation was approved in June. Coaker had resigned from the cabinet before the election and, having decided to take the FPU out of politics, dissolved the 1919 alliance (though he himself was returned). Discontent within the administration had apparently ebbed, and Squires seemed to be riding high.

Within days the situation began to unravel as the opposition gathered evidence of government misdoings. First, Cashin alleged that public funds had paid a minister’s electioneering expenses. Charges were brought against Alexander Campbell, minister of agriculture and mines, whose department had funded relief projects that were used for the prime minister’s and Campbell’s political advantage. Then it transpired that the Department of the Liquor Controller, which had turned into a lucrative bootlegging operation run by John Thomas Meaney, had been giving Squires substantial “loans,” most of which had not been repaid. Politics was an expensive business, Squires liked an expensive lifestyle (he sold insurance and lent money, when he had any to lend, to supplement his income), his newspaper relentlessly lost money, and subsidies had become essential. Warren led a cabinet revolt, and an unrepentant Squires, who refused to confirm or deny charges that he had received kickbacks from mining companies and made private use of public funds, resigned as prime minister on 23 July.

Warren, the new prime minister, established an inquiry into the allegations against Squires and Campbell. He asked the British government to recommend a commissioner whose impartiality would be unquestioned. Thomas Hollis Walker, kc, was given the necessary authority and sent to Newfoundland; his report, submitted in March 1924, declared that the accusations were largely true. Warren laid criminal charges against Squires, Campbell, Meaney, and a civil servant, and ordered their arrest two days before the legislature was scheduled to open on 24 April. By the time the house met, however, Squires had been bailed, and with the support of four defectors and the opposition, he brought down the government on a no-confidence vote.

After a complicated political hiatus, an election took place on 2 June. The Liberals were led by Albert Edgar Hickman*. Squires did not stand but he backed, personally and through his new newspaper, the Daily Mail (St John’s), nine “true Liberals,” thus signalling that he was by no means a spent political force. He and his supporters brazenly argued that the Hollis Walker report was no more than a shabby political manoeuvre to remove him from office. There were also those who saw the attack on Squires in sectarian terms, as Rome against Orange. These criticisms, thin as they may have been, were reinforced by a grand jury’s refusal to indict him on charges of larceny.

The new government, which included Liberals, former members of Morris’s People’s Party, Catholics, and conservatives with mercantile interests, was led by Walter Stanley Monroe*. Further charges were brought against Squires, this time for failing to pay income tax since 1918. Squires fought hard, and lost. He was fined – he allowed his car to be seized and auctioned – but eventually filed his returns. He remained a public figure, and when he let it be known that he intended to lead the Liberals in the next election, his supporters regrouped. Coaker, who loathed Monroe and the effects of his policies on the fishery, agreed to back Squires once again. Defections placed the government in a precarious position, and in May 1928 nine members formed a separate pro-Squires group, though Hickman remained leader of the opposition and headed a separate Liberal faction.

By the time that the election campaign began in earnest that fall, Hickman had been shunted aside and Squires had emerged as the sole Liberal leader. He had the support of Coaker and Peter John Cashin*, son of his old enemy, who possessed a surname to be conjured with and came with valuable Catholic credentials. The remaining government members attempted to create a new image by installing Frederick Charles Munro Alderdice as leader; his followers would eventually become the United Newfoundland Party. Not surprisingly, they assailed Squires as an untrustworthy crook, and Coaker as a menace. Squires in turn attacked the government’s record, and promised freedom from “Tory mercantile control” as well as lower taxes and industrial development. Most important, a newsprint mill would be built on the Gander River. Just as he had put the “Hum on the Humber,” he would put the “Gang on the Gander.” A clever touch was to produce and circulate a gramophone record of one of his campaign speeches.

Squires decided to run in the relatively safe Humber district, thereby dashing the hopes of Joseph Roberts Smallwood*, who had been nursing the seat. For Squires, the personal and party victories were emphatic. He was elected by a landslide; the Liberals won a 16-seat majority and 55 per cent of the popular vote. It was an astonishing comeback, confirming his charisma, energy, and mastery of electioneering. His government took office on 17 Nov. 1928. Squires was minister of justice as well as prime minister; the cabinet included Barnes (colonial secretary), Cashin (finance), William Wesley Halfyard* (posts and telegraphs), and Frederick Gordon Bradley*, Campbell, Coaker, and Harris Munden Mosdell* (all without portfolios). It was known to some as “the Cabal of all the talents.” Squires, who had received a kcmg in 1921, would be appointed to the Privy Council in 1930.

A period of conservative rule under Monroe had done little to stabilize finances, and the economy remained fragile. Within a year of Squires’s victory, moreover, Newfoundland was dealing with the impact of the Great Depression. By the end of the 1931–32 financial year, the value of exports had dropped by a third and the price of fish by half. Revenue fell by over 20 per cent, but the need for public relief plus the heavy expense of servicing the debt – which had increased by a quarter – made it difficult to reduce expenditure. Misery now engulfed the country. There seemed to be two possible ways to ease the situation. One was to implement the Gander project; the other was to sell Labrador, unequivocally part of Newfoundland since the 1927 ruling by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council [see Sir Patrick Thomas McGrath*]. Neither would come to pass.

The Gander project was a brainchild of the Reid Newfoundland Company, which controlled the required timber limits. A developer was needed, and by 1930 there was an agreement in principle with the Dominion Newsprint Company, part of the American Hearst publishing empire. Squires considered the deal overgenerous to the Hearsts, who wanted a substantial government guarantee and, it was suspected, were not negotiating in earnest. He also thought that if the Hearst deal failed, the faltering Reid company might sell off its Gander timber rights to the owners of the Humber mill, thereby wiping out any chance of another development. As a result, the government intervened to stop the Reids from alienating their limits while investigation of the mill’s possibilities continued. The attempt to revoke the Reids’ timber licences failed and the prospect of another newsprint plant disappeared. Squires was bitterly criticized for his handling of this issue, and with some justice. But the likelihood of a mill being built during the depression was remote, and the effort to take back the licences was well intentioned, even if mismanaged.

As for Labrador, informal talks about a sale to Canada had taken place during Squires’s first administration. In 1931 serious negotiations were held between a Newfoundland delegation and the government of Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett*. The territory was offered for $110 million. Squires, who distanced himself from the idea, did not take part in the discussions. Canada, also trying to cope with the depression, rejected the deal.

The economic and financial noose tightened. Preoccupied with survival, the government maintained minimal public services. Squires refused to consider even partial default on interest payments, and concentrated on retrenchment, which increased public hardship, and on finding money where he could. Cashin’s budget of April 1931 introduced deep cuts in expenditure; the opposition quickly pointed out that Liberal members were still lined up at the trough. The government’s confidence that it could stay the course was rudely disturbed when, in May, an attempt to float another loan failed, and bankruptcy became an immediate possibility. Squires and Cashin went to Ottawa. Under pressure from Bennett, the four Canadian banks operating in Newfoundland agreed to make a loan. The stringent conditions included the appointment of a special financial commissioner, Sir Percy Thompson of the British Board of Inland Revenue. More severe cuts in government expenditures followed, and a Montreal businessman, Robert James Magor, was hired to look into the operation of the railway, the telegraph system, and other government services. But there was little anyone could do to alleviate the crisis, and the government-controlled Newfoundland Savings Bank almost collapsed in November. By the end of the year Squires and Cashin, as well as Thompson, were again desperately looking for financial assistance. The banks agreed to a final loan on 31 December, forcing draconian conditions that constituted a form of receivership.

There were calls for a national, or commission, government, and for a royal commission of inquiry. The unemployed in St John’s demanded higher dole payments. The crisis, however, did not produce a united front. The conservatives of the United Newfoundland Party had little interest in a coalition and wanted the detested Squires and his cronies thrown out of office; the prime minister had little time for his “Tory” foes. But his hold on power was less sure than he may have thought. Early in February 1932 Cashin resigned as finance minister, and detonated a political explosion. He accused Squires of falsifying Executive Council minutes to cover up fees paid to himself and his constituency account from public funds – including the sum of $5,000 a year from the War Reparations Commission (which Squires headed), a particularly sensitive issue since veterans’ pensions were already threatened. Campbell was accused of income-tax evasion and other misdeeds, and another minister of forgery. It is little wonder that on 11 February Squires was roughly handled by an angry crowd of unemployed workers who pushed into his office at the courthouse.

Alderdice demanded that the accusations be investigated by a committee of the House of Assembly. Characteristically, Squires evaded the issue by moving that they be examined by Governor Sir John Middleton – a clever tactic since, in effect, Middleton was being asked to verify that he had been deceived. Squires was also trying to buy time, but if he thought the scandal would fade away, he was badly mistaken. The governor’s conclusion that there had been no falsifications convinced no one. Government members began to defect, and attacks from both Cashin and the opposition intensified. A large and noisy public meeting in St John’s on 4 April, organized by politicians, clergymen, businessmen, and opponents of the government, passed a resolution demanding a full inquiry. The next day merchants closed their premises and a huge crowd made its way to the Colonial Building, where the house was in session, to present a petition that Cashin’s charges be proved or disproved. Just as the house was debating a motion to refer the petition to a committee, the demonstration exploded into a riot. The Colonial Building was vandalized, windows were broken, fires set, and files destroyed. Squires, his wife, two other government members, and Smallwood were lucky to escape unharmed, and Squires went into hiding.

Cashin had declared that the prime minister would resign; Squires refused to do so, certain that the mob had been incited by political enemies. Instead, when the house resumed business on 19 April, he announced that there would be an early election. A committee was appointed to ascertain what might be done to carry out the citizens’ petition, but it never reported. The most significant piece of legislation passed during the remainder of the session gave Imperial Oil a 15-year monopoly on the sale of petroleum products in return for a loan which staved off default for another six months.

The Liberals fielded a full slate of candidates on 11 June, but the country had clearly had enough of them: Alderdice took 24 of the 27 seats. Squires was defeated in Trinity South and Lady Squires in Twillingate. This general election was the last to be held in Newfoundland for 14 years.

The royal commission responsible for examining Newfoundland’s future, which many of Squires’s opponents had long advocated, was appointed in February 1933. The former prime minister gave no evidence but vigorously protested the recommendation that the country should be administered by a commission established by the British government. The recommendation was implemented in 1934. For some years he remained in the background, practising law in partnership with Louise Maude Saunders and working his farm (now part of Bowring Park) west of St John’s. The family was, by all accounts, short of money. Squires would not accept that his political career was over. Indeed, he apparently thought that he could be the centre around which resistance to the commission of government – in his view, the Tory Party in disguise – could coalesce. In January 1936 he treated Governor Sir David Murray Anderson to a lengthy analysis of the government’s failings and argued that if an election were held, he would win hands down. In May 1937 he visited the British secretary of state for dominion affairs, Malcolm MacDonald, to present himself as the potential leader of the opposition to the commission. His attitude, noted MacDonald, was reminiscent of John Pym addressing Charles I, and his frame of mind was “rebellious.” That year Squires acted for the Newfoundland Lumbermen’s Association, a loggers’ union, in a major strike, and at least one outport asked for his help in lobbying the government for assistance.

Squires’s second comeback did not materialize. The commission was firmly entrenched if unpopular, war intervened, and his health began to fail. He was confined to his house for more than a year before his death in March 1940. The state funeral was attended “by an immense gathering,” the long procession being headed by veterans of World War I.

Coaker described Squires as “a politician rather than a statesman.… In my opinion the cleverest politician the country has produced. His energy was astounding.… Hard work and tongue ability made him what he became.” Had he allowed “conscience to be his guide he would have taken a foremost place amongst the great public men of Newfoundland.” On this reading, Squires was a man of talent and ability who allowed ambition and power to blunt his moral sense. F. G. Bradley later called him “a flashing tragedy.” He can also be seen as the outport boy who never fitted in with the St John’s elites: resenting their assumption of power and privilege, he tried to best them politically while imitating their expensive social mores by, for instance, sending his sons to school in England. In his single-minded drive to the top, Squires practised the often unscrupulous and highly partisan style of patronage politics then common in North America. He made many enemies and few firm allies, even in his own party; indeed, he reportedly said that “he never knew for sure when he went to bed in the evening if he would still be Prime Minister when he awoke in the morning.” By overstepping the limit of what was acceptable by the standards that prevailed in Newfoundland public life, which were hardly strict, he became a scapegoat for his country’s collapse in the early 1930s. To be fair, by the time Squires came to power Newfoundland’s future was already precarious, and he cannot be blamed for the economic disasters of the interwar period. But he had the chance and the ability to steady the situation and to provide much-needed leadership; this he signally failed to do.

Memorial Univ. of Nfld, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Arch. and Special Coll. (St John’s), mf-137 (Sir Richard Squires papers). RPA, GN 8, Richard Anderson Squires sous fonds. Melvin Baker, “Newfoundland in the 1920s”: www.ucs.mun.ca/~melbaker/1919-28.htm (consulted 11 Feb. 2013); “The second Squires administration and the loss of responsible government, 1928–1934”: www.ucs.mun.ca/~melbaker/1920s.htm (consulted 11 Feb. 2013). I. R. Carter, “The Newfoundland general election of 1928” (ba thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1991). W. F. Coaker, Past, present and future: being a series of articles contributed to the “Fishermen’s Advocate,” 1932; together with notes of a trip to Greece 1932 ([Port Union, Nfld, 1932]). L. R. Curtis, “I have worked with two premiers,” in The book of Newfoundland, ed. J. R. Smallwood et al. (6v., St John’s, 1937–75), 3: 144–52. R. M. Elliott, “Newfoundland politics in the 1920s: the genesis and significance of the Hollis Walker enquiry,” in Newfoundland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: essays in interpretation, ed. J. [K.] Hiller and P. [F.] Neary (Toronto, 1980), 181–204. J. K. Hiller, “The career of F. Gordon Bradley,” Newfoundland Studies (St John’s), 4 (1988): 163–80; “The politics of newsprint: the Newfoundland pulp and paper industry, 1915–1939,” Acadiensis, 19 (1989–90), no.2: 3–39. LAC, “Lady Helena E. (Strong) Squires”: www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/women/030001-1330-e.html (consulted 11 Feb. 2013). I. D. H. McDonald, “To each his own”: William Coaker and the Fishermen’s Protective Union in Newfoundland politics, 1908–1925, ed. J. K. Hiller (St John’s, 1987). P. [F.] Neary, Newfoundland in the North Atlantic world, 1929–1949 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1988); “That thin red cord of sentiment and of blood: Newfoundland in the Great Depression, 1929–1934” (typescript, [1988?]; 2 copies at Memorial Univ. of Nfld, Centre for Nfld Studies). S. J. R. Noel, Politics in Newfoundland (Toronto, 1971). Patrick O’Flaherty, Lost country: the rise and fall of Newfoundland, 1843–1933 (St John’s, 2005); “A portrait of Richard Squires” (paper presented to the Nfld Hist. Soc., 27 April 2006; copy at Memorial Univ. of Nfld).

James K. Hiller, “SQUIRES, Sir RICHARD ANDERSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. , University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/squires_richard_anderson_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/squires_richard_anderson_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | James K. Hiller |

| Title of Article: | SQUIRES, Sir RICHARD ANDERSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |